All known Royal Cache DB320 shabti types, shabti boxes and papyri

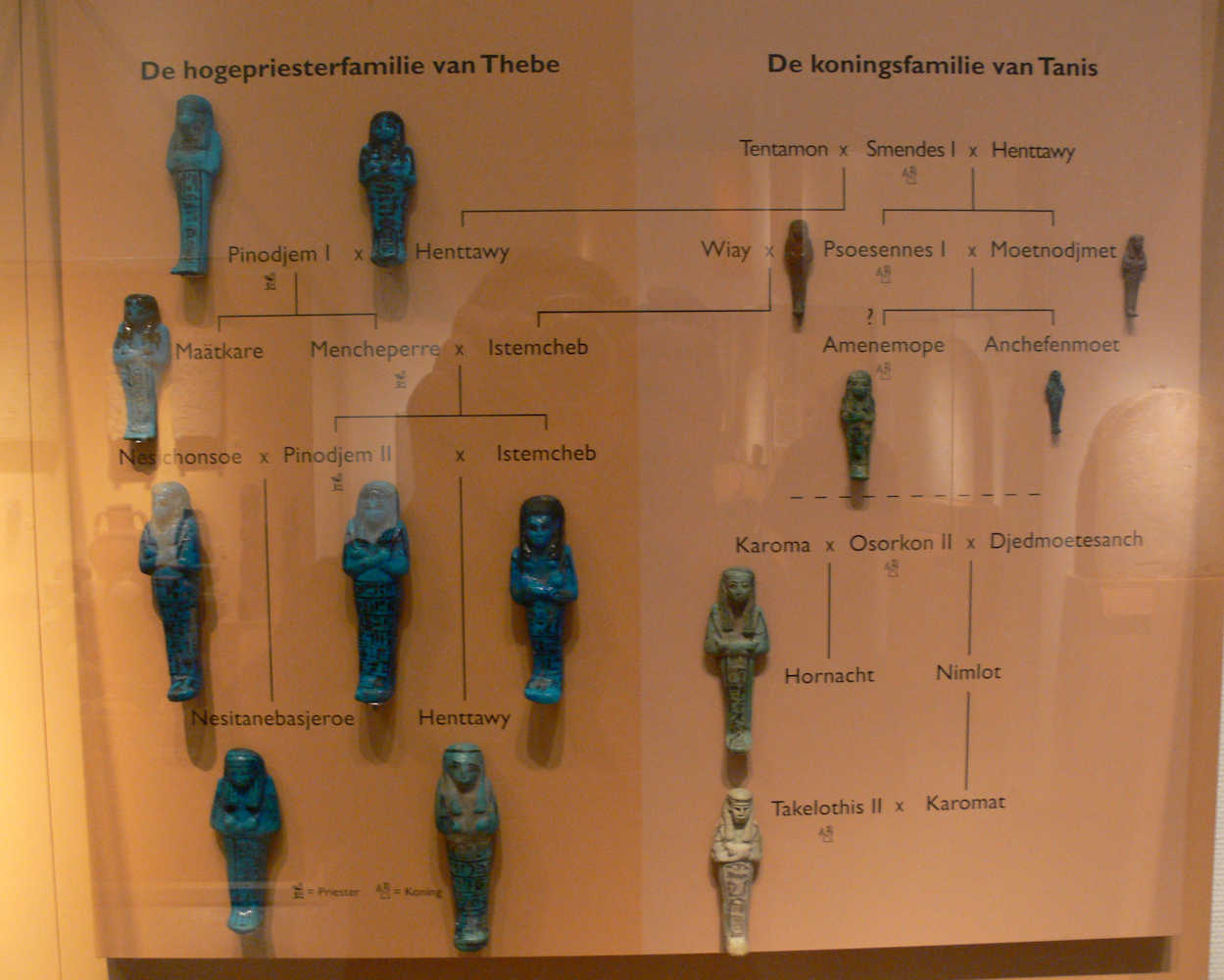

Pinedjem I high priest and later pharaoh of the south

Henuttawy A his wife

Maatkara their daughter

Masaharta their son

Tayuheret wife of Masaharta

Pinedjem II grandson of Pinedjem I

Isetemkheb D sister and wife of Pinedjem II and granddaughter of Pinedjem I

Nesykhonsu A his niece and second wife

Nestanebetisheru daughter of Pinedjem II and Nesykhonsu A

Djedptahiufankh possibly the husband of Nestanebetisheru

Left: Gaston Masparo lounging on the so-called “Masparo’s bench” at the right side of the tomb entrance (1882)

Middle: The discoverer and robber Ahmed Abd-er-Rassul at the tomb entrance, 30 years after his discovery (1902)

Right: Funerary items from the Royal Cache DB320 (officialy found, explored and cleared in 1881)

This page shows all shabti types found in Royal Cache DB320. The sections are per owner and based on the divergent form of the shabtis

Although more than fifty persons were interred, shabtis have been found for only ten of them. The mummies of the others were reburied without the shabtis they probably had in their original tombs

The source for this research

The high priests of the 21st dynasty reburied the mummies of the old gods (including pharaohs Tuthmose III, Seti I and Ramses II) in a secret collective tomb (also refered to as Cache or Cachette), because a number of kings’ tombs had been defiled and plundered by thieves looking for treasure. The high priests also used this secret spot as a final resting place for themselves and their loved ones. Only a few valuables belonging to the interred royals were found in the tomb. The high priests have probably re-used the missing pieces or stolen them to enrich themselves or to maintain the rule over the south

Menkheppera, a son of Pinedjem I, is missing from the tomb. Menkheperra was in office for no less than 55 years, 42 of them as pharaoh and ruler of the south. During his reign, the clearing out of kings’ tombs continued and must have yielded a lot of gold and silver. It is possible that he took part of these treasures with him to his own final resting place. His tomb and the one belonging to his wife have not been discovered yet

The discovery of the collective tomb in 1881 gives us insight into the things that were interred with the high priests and their loved ones. This may have included 4000 shabtis, Maspero estimated the total in 1881 around 3700. A number of them were sold illegally even before the tomb was officially opened. Others were lost, trampled or sold to tourists and museums. The Egyptian museum itself had a shop where shabtis could be bought. The remaining shabtis and fragments are now in museums, universities and private collections

In 2014 the Cairo museum had 492 Royal Cache shabtis on display, 382 workers and 110 overseers. It is unknown whether any shabtis or fragments still exist in locations that are not publicly accessible

In Les Momies Royales de Deir El-Bahari 1899, pg 590-591 Maspero writes that at least 20 ushebti boxes were found, of which 12 intact and the others crushed and fragmented by the weight of the shabti’s. He mentions 2 boxes for Pinedjem I (pictures below), 2 for Henuttawy (pictures below), 2 for Maatkara (pictures below), none for Masaharta, fragments for Tayuheret, 2 for Pinedjem II, fragments for Isetemkheb D (restorated by the museum, pictures of 4 boxes), 1 for Nesykhonsu (she might have usurped one or two boxes from Isetemkhebit D (see pictures)), 3 for Djedptahiufankh (only one box is known to me, see picture) and fragments of a box or boxes for Nestanebetisheru

This overview would not exist without

Niek de Haan who got me enthusiastic about the blue shabtis

Edward Loring (sadly, Edward passed away in 2015) who had taken to heart Egypt and the 21st dynasty. From him I received detailed photos of DB 320 shabtis in the Cairo Museum

Prof. Andrzej Niwinski, who, with his impressive research and publications, has compiled an incredible amount of detailed information about the Third Intermediate Period, which I gratefully use to support my research

Glenn Janes who made it possible for me to wrap up my project. He shared materials with me that enabled me to verify earlier research and fill in gaps

The Theban Mummy Project presented by Wm. Max Miller were you can find awesome photo’s, background stories and references

Andreas von dem Berge who has provided professional 3D films of many shabtis with special provenance or historical context, including many from the Royal Cache and Bab el Gasus

Thank you all!

Please keep in mind that the dates of the specimens given here may be off to a certain degree. Various scholars are using other dates that in some cases differ by decades. I have included the dates I deem most probable based on various publications. If you have any questions, comments or improvements, please send an email to info@ushabtis.com

Below you will find an overview of the shabtis, followed by some background information on the discovery of the tomb, Maspero’s notes and the location of the Royal Cache

Relevant publications

Les momies royales de Deir El-Bahari, 1889 by G. Maspero Maspero, Gaston (1846-1916)

Cercueils des Cachettes Royales by M. Georges Daressy, 1909

The Royal Mummies (1912) by Smith, Grafton Elliot (Sir; 1871-1937)

Catalogue général des antiquités égyptiennes du Musée du Caire N° 61051-61100

21st Dynasty coffins from Thebes: Chronological and typological studies, by Andrzej Niwinski 1988

– outstanding standard reference publication for coffins of Thebes from the Third Intermediate Period

Contribution à l’étude de l’Amdouat: Les variantes tardives du Livre de l’Amdouat dans les papyrus du Musée du Caire by Sadek, Abdel-Aziz Fahmy 1985

– extensive reference publication of the Amdouat papyri in Cairo

Studies on the illustrated Theban Funerary Papyri of the 11th and 10th Centuries B.C. by Prof. Andrzej Niwinski, 1989

– another amazing work from this author. In my overview I have taken the liberty of showing the notes from his publication to quickly get a complete overview of the papyri that can be attributed to a shabti

Burial Assemblages of Dynasty 21-25: Chronology – Typology – Developments by David Aston 2009

– very complete and standard reference of the burial assemblages of Dynasty 21-25

Funerary Statuettes and Model Sarcophagi, Percy E. Newberry 1930, 1937, 1957

Fascicule 1, Le Caire, 1930, CG 46530-48273

Fascicule 2, Le Caire, 1937, CG 48274-48575

Fascicule 3, Le Caire, 1957, Indices and Planches

– standard reference for shabtis in the Cairo Museum

Photo: VB

Hi! My name is Gaston Maspero and I was the first one to research the Royal Cache shabtis. You can still see them in the Cairo Museum. Just click my photo to see a private impression from 2004

See also interesting recent research by a Spanish and Egyptian team under supervision of the Supreme Council of Antiquities of Egypt (SCA)

A lecture on the discovery of the Royal Cache by Chris Naunton is also worth watching

Royal Mummies found in Deir El-Bahari. The Illustrated London News 1882

Photo: Twitter

Pinedjem I – pAy-nDm I

Also known as Paynedjem, Pajnedjem, Pinezem, Pinudjem

Period c. 1070 to 1032 BC

Ranke I, pg. 114, 10

High priest of Amon in Thebes and later ruler from the border city Tayu-djayet (el-Hiba). Tayu-djayet marked the division of the land between the high priests of Amon in Thebes and the kings of Egypt in Tanis. During his reign he reinforced control and proclaimed himself pharaoh over the south of Egypt. His son, Psusennes I, became pharaoh in the north (Tanis). Pinedjem lived to 60 years of age. His original tomb is unknown.

The shabtis of Pinedjem I are not large, but they are among the most beautiful from the 21st dynasty. In the Cairo Museum I have counted 23 workers and 3 overseers

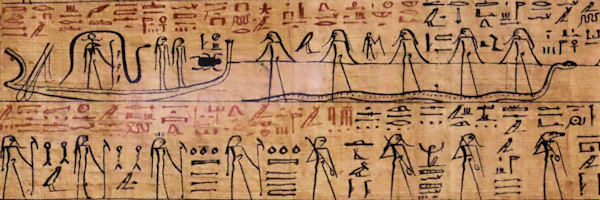

Funerary papyri attributed by Sadek, BA S .R. VII .11492, Cairo 114 Niwinski. Numbers in Sadek ‘Musee du Caire, 11 et 4761’, see Amduat papyrus Pinedjem II

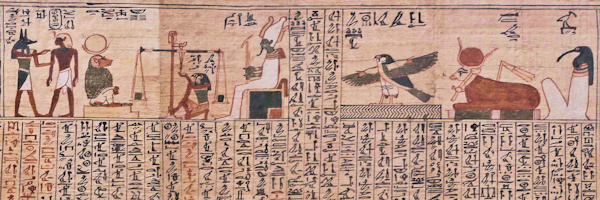

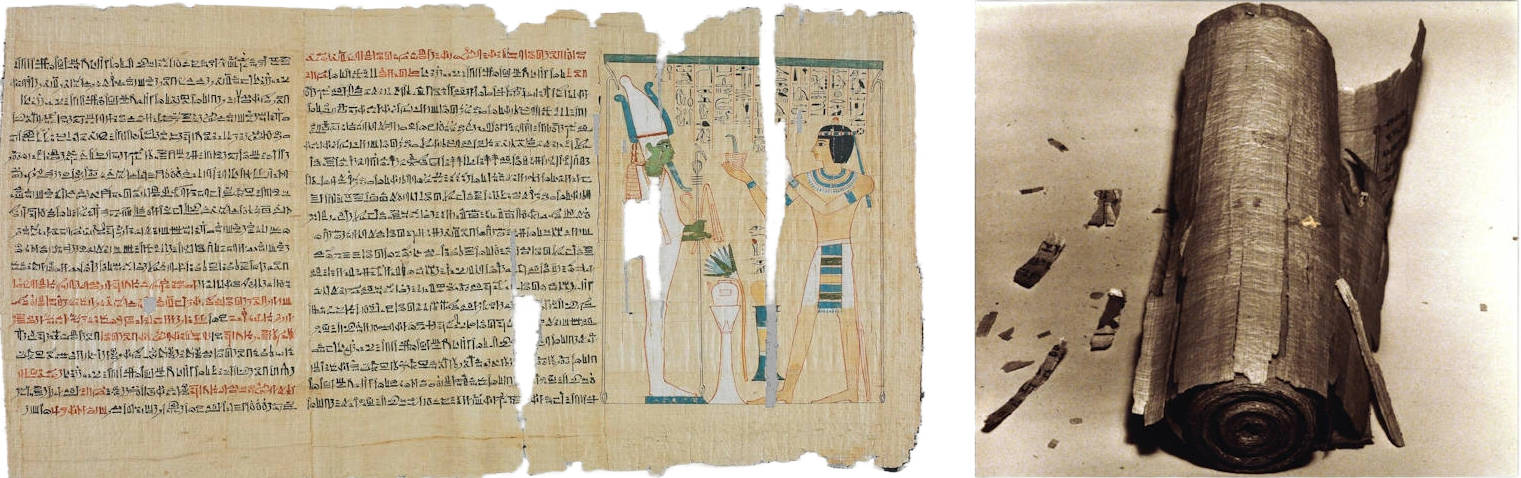

BD S.R.VII.11488 – CG 40006, Cairo 111

Book of Dead for Pinedjem I

See also Seeber 1976, p.210; Saleh and Sourouzian 1986, No 235; Maspero 1912, No 4761 and CAIRO katalog Die Hauptwerke im Ägyptischen Museum Kairo, 1986, no. 235

Panorama view, VB 2021

Pinedjem I

Mummy on the photo was in the Boulaq Museum. The mummy has been missing since the late 19’th century. Rumors that it might be at the Qasr el Einy Medical Facility in Cairo

Photo: Émile Brugsch/Museum of New Zealand. Research

Pinedjem I

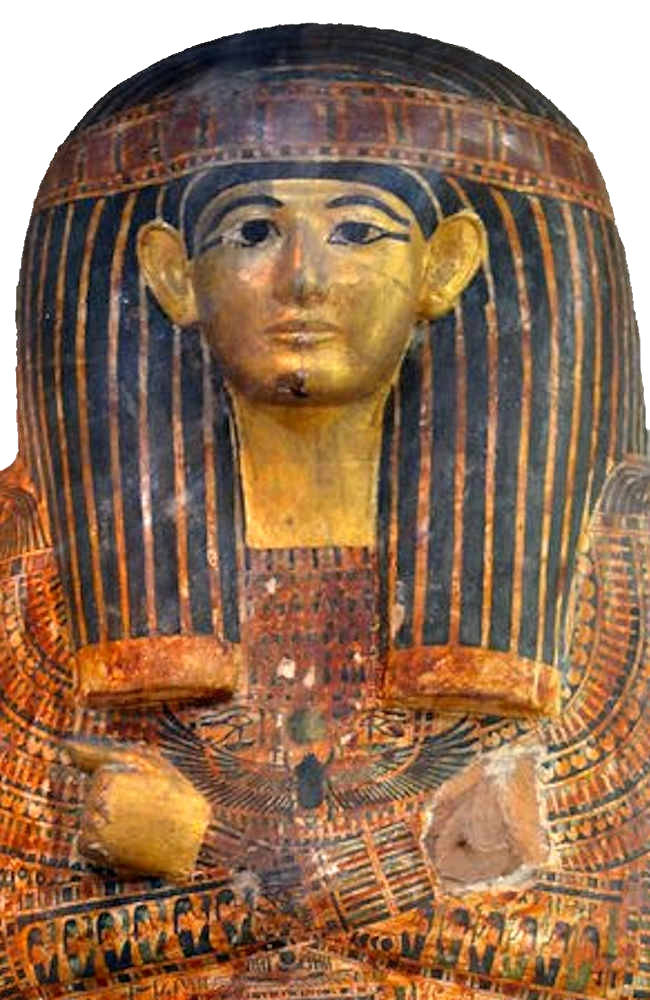

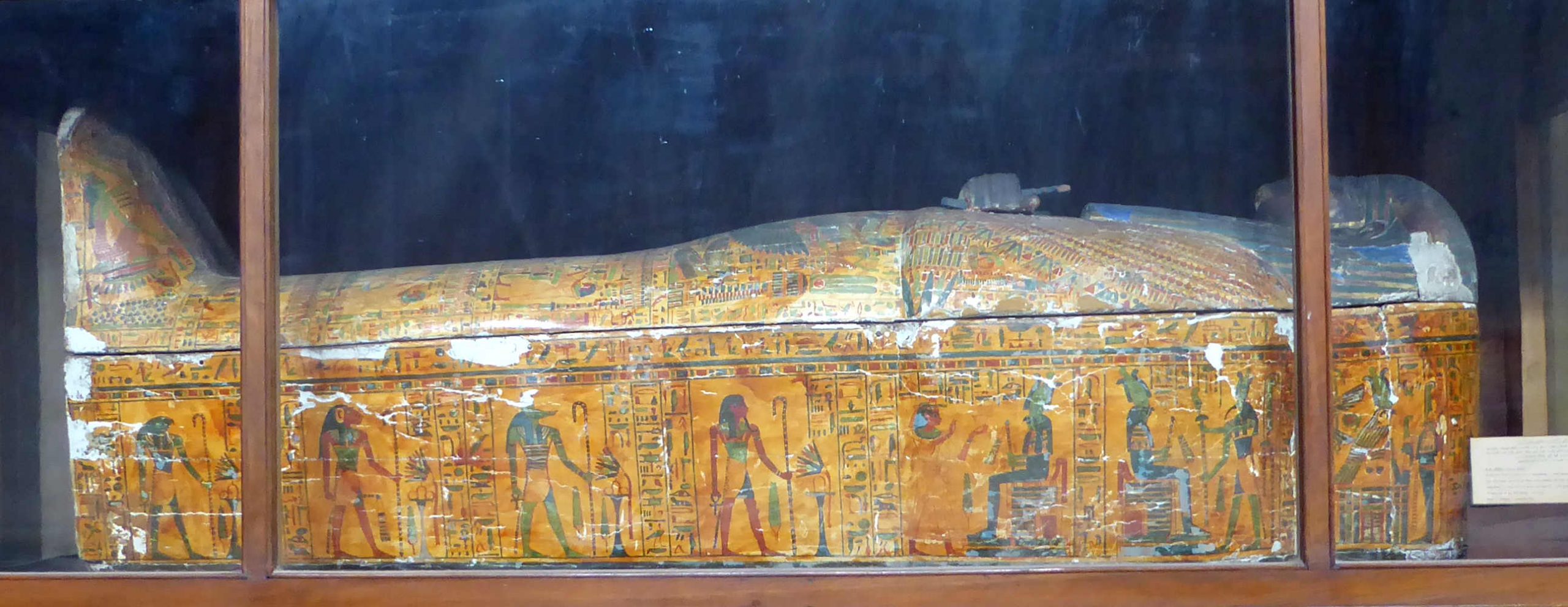

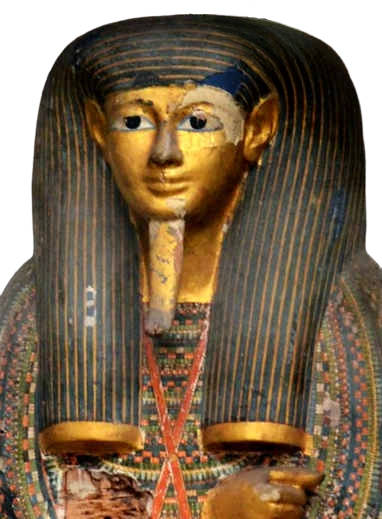

Inner coffin Cairo Museum CG 61025

Photo: Ceras. Research

Pinedjem I

Outer coffin ursurped from Tuthmosis I

Cairo Museum CG 61025

Photo: Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, Southern California

Pinedjem I

Worker 1

Faience, 13.6 cm

21st Dynasty, 1026 BC

Dutch private collection

Photo: VB

In the cartouches of the P1’s we often see his birth name “Pinedjem”, but also his throne name “Kheperkhaura”. In this photo (AB 2022), with sides and backs of the shabtis, both titles are visible.

All around movies of two other workers, here and here

German private collection

Courtesy AB 2022/2024

Pinedjem I

Worker 3

Faience, 10.7 cm

21st Dynasty, 1026 BC

Royal Museums of Art and History, Brussel E.5556

Photo: VB

All around movie of another worker with the wig of Worker 5

German private collection

Courtesy AB 2022

Pinedjem I

Worker 5

Faience, 11 cm

21st Dynasty, 1026 BC

Pierre Berge, May 21,

2014 Lot 43

Photo: Pierre Berge

It is a mystery to me why the quality of the faience of the Worker 5 series is so different from other shabtis of Pinedjem I and this period. It seems as if they were made under special circumstances

All around movies of two other workers, number one, number two (with wig Worker 3)

German private collection

Courtesy AB 2022

Pinedjem I

Overseer 1

Faience, 11.7 cm

21st Dynasty, 1026 BC

British Museum, London EA 18588

Photo: British Museum

All around movie of another exceptionally well-preserved overseer

German private collection

Courtesy AB 2022

Pinedjem I

Overseer 2

Faience, 12.3 cm

21st Dynasty, 1026 BC

Sotheby’s New York June 20th 1990, ex. Breitbart Collection, lot 16

Photo: GJ

Second shabti box Pinedjem I (front)

Second one of the two boxes

Mummification Museum Luxor JE 26253B

Photo: VB 2017

Exterior coffin Pinedjem I ursurped from Tuthmosis I. Cairo Museum CG 61025. Photo: Cesras – Edward Loring

Georges Daressy’s Cercueils des cachettes royales, 1909. Research

Henuttawy A – Hnwt-tAwy A

Duat Hathor and Mistress of the Two Lands (Queen)

Also known as Henouttawy, Honittaoui

It is assumed that Henuttawy is a daughter of Ramses XI, the last king of the 20th dynasty. She becomes Pinedjem I’s first wife, has many titles and plays an important role at court. Originally she has her own tomb in an unknown location, and before she is interred in the secret cachette her mummy boxes are stripped of the gold that covered them.

In the Cairo Museum I have counted 41 workers and 7 overseers.

Funerary papyri

BD S.R.IV.955 – JE 95856 – CG 40005, Cairo 36

Book of Dead for Henuttawy A, Length 367 cm, Height 45.5 cm

See Analecta Papyrologica by Moamen Othman, Ahmed Tarek and Mohamed Abdelrohman

Panoramaview, VB 2022

BA S.R.IV.992 – JE 95887, Cairo 47

Amduat papyrus for Henuttawy A, Length 143 cm, Height 33.5 cm

Panoramaview, VB 2022

Pontificate Menkheperre c. 1051 – 1001 BC, see Aston pg. 225

Henuttawy A

Mummy CG 61090

Photo: Patrick Landmann, ACI/Science Photo Library, Ceras

Upper part interior coffin of Henuttawy A. Cairo Museum JE 26224 / CG 61026. The decoration of the coffin is largely stripped of

Photo: Edward Loring

Henuttawy A

Worker 2

Like worker 1 with extra writing on sides and back

Faience, estimated 11.7 cm

21st Dynasty, 1040 BC

NationalMuseet, Kopenhagen

Photo: VB

Henuttawy A

Overseer 1

Faience, ca. 10.5 cm

21st Dynasty, 1040 BC

Cairo Museum

The attribution to Henuttawy is under research by Niek de Haan.

Photo: Edward Loring

Henuttawy A

Overseer 2

Faience, 11.5 cm

21st Dynasty, 1040 BC

British Museum, London EA30398

Photo: VB

All around movie of a pristine overseer

German private collection

Courtesy AB 2024

Henuttawy A

Overseer 3

Faience, 11.9 cm

21st Dynasty, 1040 BC

Boisgirard – Antonini,

June 18, 2014 Lot 1

Dutch private collection

Photo: NH

Photo of front and back

Courtesy: NH 2022

Second shabti box Henuttawy A – front

Second one of the two boxes

Cairo Museum JE 26272 A or B

Photo: VB 2015

Interior coffin of Henuttawy A. Cairo Museum JE 26224 / CG 61026. The decoration of the coffin is largely stripped of. Photo: Edward Loring

Georges Daressy’s Cercueils des cachettes royales, 1909. Research

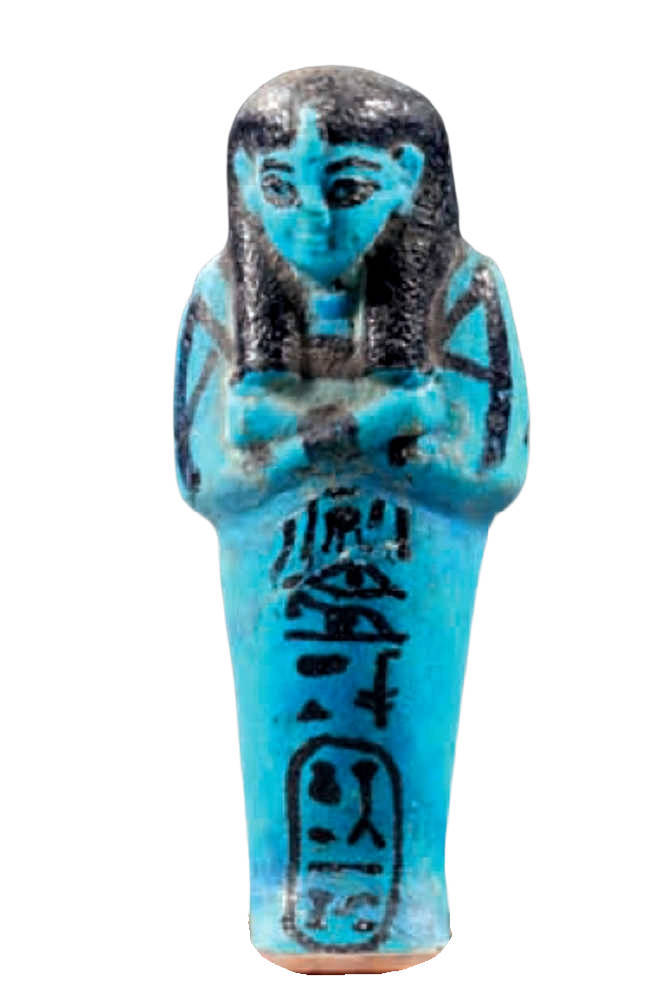

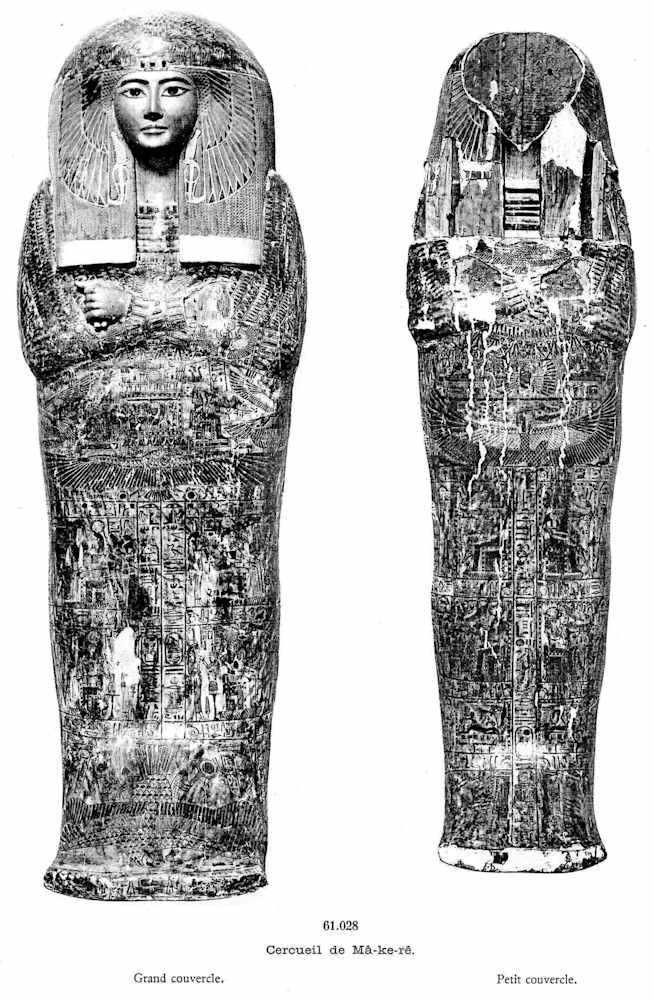

Maatkara – mAat-kA-ra

God’s Wife of Amun

Also known as Maatkare, Makeri, Mutemhat, Mutemhet, Kamara

Maatkara was the eldest daughter of Pinedjem I and Henuttawy A and became the most powerful woman in the south of Egypt. Her position was equal to that of the high priest of Amon. Maatkare received the title of ‘Divine Adoratrice’: God’s Wife of Amun.

Her original burial place is unknown; her mummy was found in the Royal Cache cache along with her coffins, shabtis and other mummies from her immediate family. A small mummy, originally thought to be a child of hers was later revealed to be that of a pet monkey. (God’s Wives were supposed to be celibate.)

In the Cairo Museum I have counted 96 workers and 14 overseers

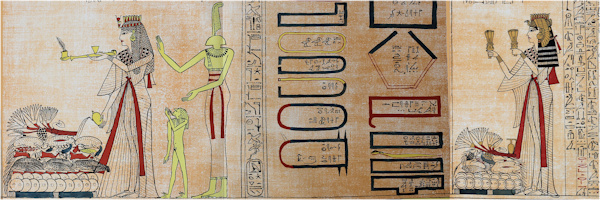

Funerary papyrus

BD S.R.IV.980 – JE 26229 – CG 40007, Cairo 43

Book of the Dead for Maatkara

Length 612 cm, height ? cm

See Le Papyrus hiéroglyphique de Kamara et Le Papyrus hiératique de Nesikhonsou

Edouard Naville, 1912

Panorama view, VB 2022

Maatkara

Photo: Patrick Landmann/Science Photo Library

See also The Royal Mummies (1912) by Smith, Plate LXXII

Research

Maatkara

Cairo Museum JE 26200. Photo: Edward Loring, Ceras

Maatkara

Worker 1, like worker 2 but light blue

In the cartouches drawn by Maspero, this version with the Maat feather is missing. It may be assumed that by the end of the 19th century they were no longer in Cairo. Two copies are known in the world, all others depict the Maat goddess. Piquant detail is that this shabti comes from the Maspero collection no. 19

Faience, 11.5 cm

21st Dynasty, 1020 BC

Dutch private collection

Photo: VB

All around movie of another worker

German private collection

Courtesy AB 2022

Maatkara

Worker 2, like worker 1 but dark blue

Faience, estimated 11.5 cm

21st Dynasty, 1020 BC

Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, New Haven YPM 6094.3

Photo: VB

All around movie of another worker

German private collection

Courtesy AB 2022

Maatkara

Overseer 1, without breasts

Unique specimen

Faience, 9.5 cm

21st Dynasty, 1020 BC

Thierry de Maigret, October 24, 2012 Lot 64 ex Charles Bouché

Photo: Thierry de Maigret

All around movie

German private collection

Courtesy AB 2022

Maatkara

Overseer 4, without breasts

Faience, estimated 12 cm

21st Dynasty, 1020 BC

Cairo Museum

Photo: Edward Loring

Maatkara

Overseer 5, without breasts,

three others in the museum have a cartouche on their skirts

Faience, estimated 12 cm

21st Dynasty, 1020 BC

Cairo Museum

Photo: Edward Loring

Box Maatkara – Mutemhat

In 2020, I photographed another box of Maatkara with two cartouches. On the left the one of Maatkara and on the right the one of her other name Mutemhat. In Porter and Moss The Theban Necropolis pg. 663 the suggestion is made that this is a shabti box (the second in their publication). Since the two boxes shown above are sufficient to house the shabtis of Maatkarte I assume that this box was used for other grave goods. Aston makes no mention of this box.

Cairo JE 26268

Photo: VB 2020

Georges Daressy’s Cercueils des cachettes royales, 1909. Research

Masaharta – mA-sA-hrT

High Priest of Amun

Also known as Masahirti

The eldest son of Pinedjem I was Masaharta. After Pinedjem had proclaimed himself pharaoh he transferred his title of High Priest of Amon to his son.

In the Cairo Museum I have counted 24 workers and 17 overseers. Masaharta’s original tomb was probably plundered in ancient times, and it is not clear whether all his shabtis date from the same period. It is assumed that there were two shabti boxes. Photos are not available.

Aston thinks that the mummy of Masaharta, damaged by robbers, was restored by the priests of the Third Intermediate Period and that possibly worker shabtis from later times were added. I see no evidence for the latter (Aston type E pg. 358 is incomparable to the types shown above). See Aston pg. 222 and 358.

Since the overseers do bear some style resemblance to shabtis from later periods, it might well be that they were added after the mummy was restored. Also, the overseer of Hennutawy A (Overseer 1) gives the impression that it might be from another time. However, for now, this is only theory and needs further investigation.

There is no funerary papyri known

The burial dates to c. 1057-1051 BC

Masaharta

Worker 1, with beard, only two with beard are known to me

Faience, 9.6 cm

21st Dynasty, 1040 BC

Dutch private collection

Photo: NH 2023

Masaharta

Worker 3, large specimen with seshed (fillet) headband

Faience, 10 cm

21st Dynasty, 1040 BC

Cairo Museum

Photo: Edward Loring

Masaharta

Worker 5, large specimen with seshed (fillet) headband

Faience, 10.5 cm

21st Dynasty, 1040 BC

German private collection

Photo: AB

All around movie

German private collection

Courtesy AB 2022

Masaharta

Overseer 1, like overseer 2 with seshed headband and bracelet

Faience, 10.5 cm

21st Dynasty, 1040 BC

Cairo Museum

Photo: Edward Loring

Georges Daressy’s Cercueils des cachettes royales, 1909. Research

Tayuheret – tAyw-Hrt

Chief of the harem of Amun-Ra

Also known as Taiouheret, Taiouhrit

Wife of Masaharta. In the Cairo Museum I have counted 14 workers and 18 overseers. Fragments of one shabti box were found. No photo available.

There is no funerary papyri known

The burial is dated to 1070-1060 BC, Aston pg. 223

Tayuheret

Worker 1, like worker 2 with vertical lines on top of wig

Faience, ca. 11 cm

21st Dynasty, 1000 BC

Cairo Museum

Photo: Edward Loring

Research

Tayuheret

Overseer 1, like overseer 2 with vertical stripes on skirt. On a few examples the name is written on the back

Faience, ca. 10,5 cm

21st Dynasty, 1000 BC

Cairo Museum

Photo: Edward Loring

Research

All around movie of another amazing example with the name written on the back

German private collection

Courtesy AB 2022

Tayuheret

Overseer 2, like overseer 1 with name of Tayuheret on skirt

Faience, ca. 10,5 cm

21st Dynasty, 1000 BC

Cairo Museum

Photo: Edward Loring

Research

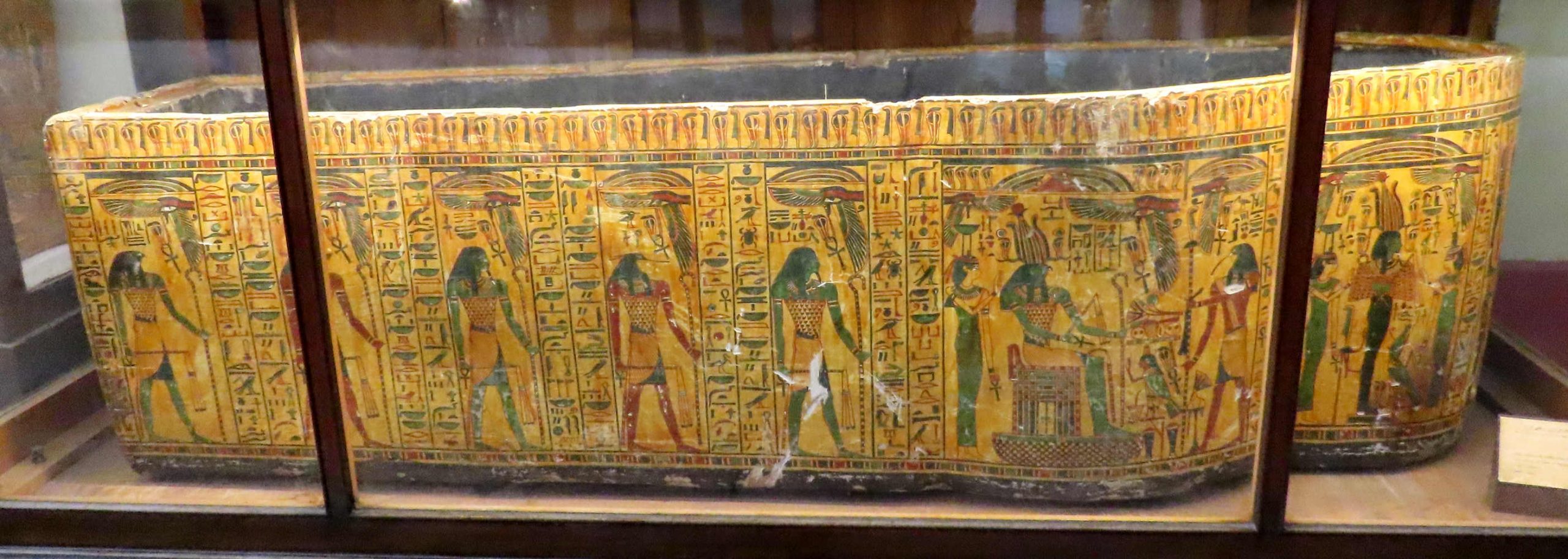

Exterior and interior coffin of Tayuheret usurped from Hatet. Cairo Museum JE 26196 / CG 61032 / SR 10344.

Photo: VB 2020

Georges Daressy’s Cercueils des cachettes royales, 1909. Research

Pinedjem II – pA-nDm II

High priest of Amun

Also known as Painozem II, Panedjem

Ranke I, pg. 114, 10

Pinedjem II was the son of Menkheppera, grandson of Pinedjem I and married to his sister Isetemkheb D and his niece Nesykhonsu. His brother Tjanefer was burried in the Bab el Gasus Cache. In the Cairo Museum I have counted 27 workers and 7 overseers. His shabtis are large and have a deep blue colour, just like the ones for his second wife, Nesykhonsu. Two shabti boxes entered the Egyptian Museum with no. JE 46943 and JE 46942 (also assumed to belong to Pinedjem II). Unfortunately I found no photos and the boxes could not be traced in Cairo

On the shabti of Pinedjem II (970 BC) the term “Ushebti” is used for the first time, and from this moment on shabtis are called Ushabtis. But in most publications (including on this website), the term shabti is usually used for the entire shabti period

Funerary papyri

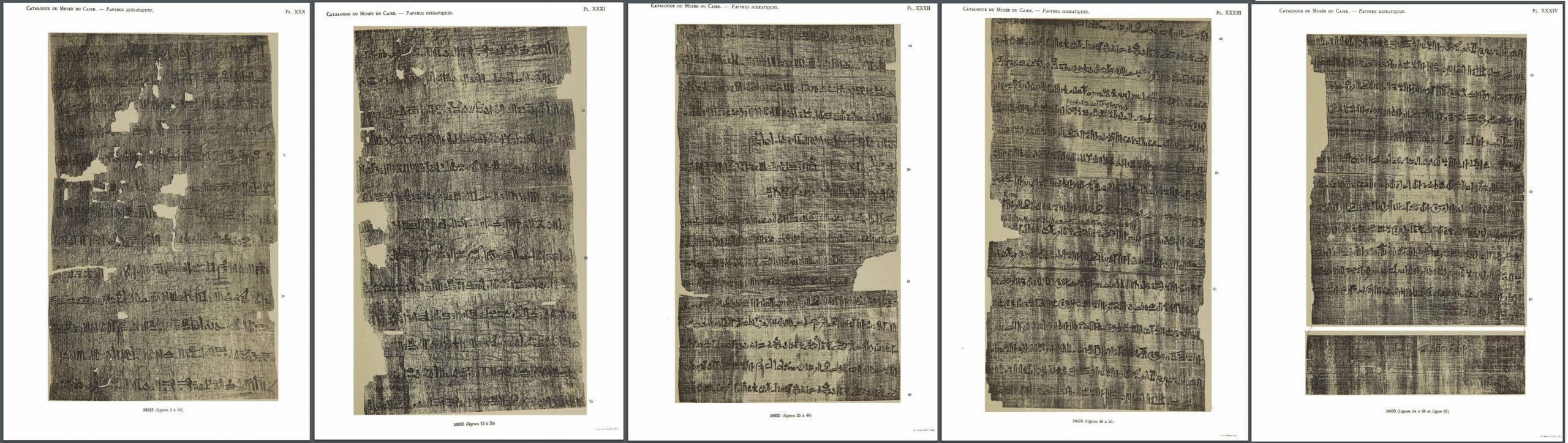

Amun decree JE 95684 – CG 58033

See Catalogue général des antiquités égyptiennes du Musée du Caire No. 58001-58036 Papyrus Hieratiques, Golenischeff 1927, plates XXX-XXXIV, see also pg. 196-209

For a legible version, see Deification decree of Amun for Pinedjem II

BD BM 10793 British Museum, London 63

Book of the Dead papyrus of Pinedjem II, on the right Pinedjem in front of Osiris

Photos © The Trustees of the British Museum

Panorama view VB 2022

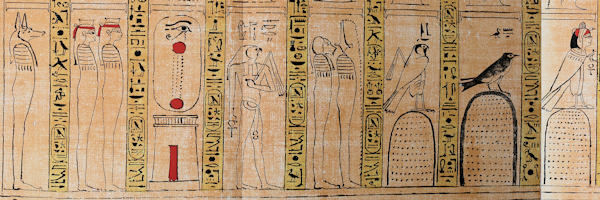

BA S .R. VII .11492, Cairo 114

Numbers in Sadek ‘Musee du Caire, 11 et 4761’

Amduat papyrus for Pinedjem II (or Pinedjem I, Sadek), Length 480 cm, height 32 cm

See Contribution à l’étude de l’Amdouat, Sadek 1985, C33 – 3 fragments on Planche 48, for short description see page 227-228, attributed to Pinedjem I (Niwinski attributed this papyrus to Pinedjem II and coffin JE 26197)

Panorama view VB 2021

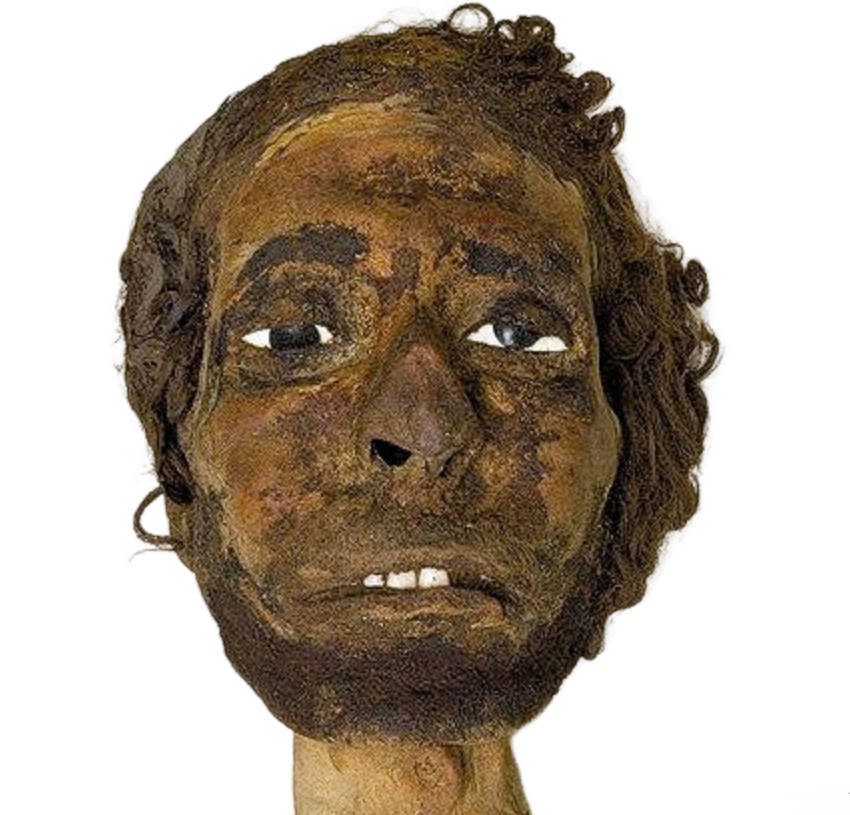

Pinedjem II

Mummy Cairo CG 61094

Photo: Perankhgroup

Pinedjem II

Gilded mummy board Cairo CG 61029, JE 26197

Photo: VB 2015

Pinedjem II

Worker 1

Faience, 17 cm

21st Dynasty, 970 BC

Dutch private collection

Photo: VB

On the worker shabtis of Pinedjem II, there is a “w” written before the hieroglyphics of the word “shabti”. The “w” is pronounced “ou”, so this is where the term “Ushebti” or “Ushabti” is first used.

All around movies of two other workers, here and here

German private collection

Courtesy AB 2022/2024

Pinedjem II

Overseer 1

Faience, 17.5 cm

21st Dynasty, 970 BC

Beaussant Lefèvre, November 15, 2013 Lot 18

Photo: Beaussant Lefèvre

Research known overseers

Georges Daressy’s Cercueils des cachettes royales, 1909. Research

Isetemkheb D – Ast-m-Ax-bit D

Chief of the Harem of Amun-Ra

Also known as Isetemakhbit, Isimkhobiou

Isetemkheb was Pinedjem II’s sister and his first wife. In the Cairo Museum I have counted 31 workers and 6 overseers. One shabti box Cairo Museum JE 26275 and second shabti box (attributed). Her her daughter Herytubekhet has been found in the Bab el Gasus cache

Funerary papyri

BD S.R.IV.525 = JE 26228 bis, Cairo 1, length 56 cm, Height 20 cm

JE 26228 without the suffix “bis” is also indicated at Cairo A, the Decree of Nesykhonsu. It is not clear to me why.

Isetemkheb D

Worker 1, like worker 2 but dark blue

Faience, 14.7 cm

The length of shabtis in this series can be up to 16 cm

21st Dynasty, 955 BC

Dutch private collection

Photo: VB

There are Type 1 and Type 2 shabtis with a different (rare for this series) register. For example, there is a single vertical register for the dark blue version and a double vertical register for a relatively large light blue one. Both shabtis were spotted in the Cairo Museum. Photo courtesy Glenn Janes

All around movies of six other workers (one, two, three, four, five and six)

German private collection

Courtesy AB 2022/2024

Isetemkheb D

Worker 2, like worker 1 but light blue

Faience, 14.5 cm

The length of shabtis in this series can be up to 16 cm

21st Dynasty, 955 BC

Dutch private collection

Photo: VB

All around movie of another worker

German private collection

Courtesy AB 2024

Isetemkheb D

Worker 3

Faience, estimated 14

The lengths also vary in this group and some are as large or even larger than Type 1 and 2

21st Dynasty, 955 BC

Cairo Museum

Photo: Edward Loring

The difference between Type 1 and 2 can be clearly seen by the right arm lying over the left. The ears are well worked out on the wig of this shabti. The series consists of shabtis with vertical and horizontal registers

Here is a comparison with horizontal registers and a large 16 cm type 1

All around movies of three other workers with horizontal registers (one, two, three)

German private collection

Courtesy AB 2022/2024

Isetemkheb D

Worker 4

Faience, estimated 11.5 cm

21st Dynasty, 955 BC

Cairo Museum

Photo: Courtesy Glenn Janes

This small version can be found in Cairo. On this picture the difference between Type 1-2 (left) and 3 (centre) can be clearly seen. These shabtis were in the display case in Cairo early this century and were photographed side by side, so the height difference is exact. Photo courtesy Glenn Janes

Isetemkheb D

Overseer 1

Faience, estimated 13.5 cm

21st Dynasty, 955 BC

Cairo Museum

Photo: Edward Loring

Isetemkheb D

Overseer 2, broad specimen

Faience, estimated 14.5 cm

21st Dynasty, 955 BC

Cairo Museum

Photo: GJ

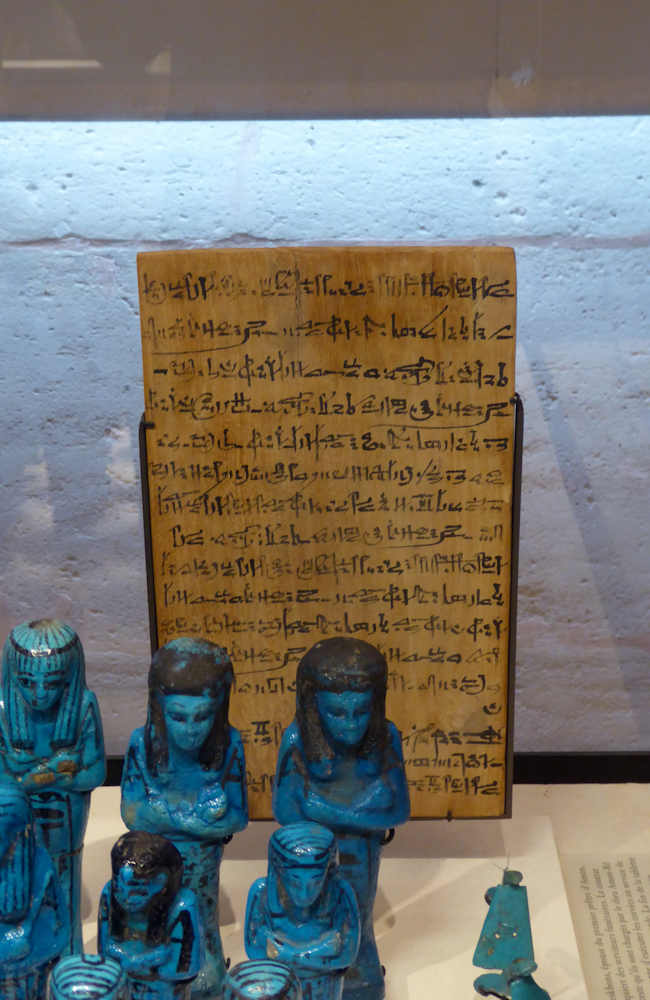

Shabti boxes Isetemkheb D

Cairo Museum JE 26275 / TR 14/12/27/3

Maybe the two boxes above (Maspero mentions that they only found crushed and fragmented material) were used for Isetemkheb. They suffered from water damage in another tomb were Isetemkhebit was interred before she was reburied in DB320. The other two might be used for Nesykhonsu who also ursurped a coffin set from Isememkheb. Maspero mentions only one box, that might by the one below with the three compartments. Maybe he ignored the other one because it does not have the style of a shabti box. Probably all boxes were restorated by the museum.

Photo’s: Cesras

Research

Georges Daressy’s Cercueils des cachettes royales, 1909. Research

Nesykhonsu A – nsy-xnsw

Also known as Neskhons, Nesikhons, Nesikhonsu, Nesikhonsou, Neschons, Nesi-Khensu, Eskhons

Ranke I, pg. 178, 20

The name means ‘The one who belongs to Khonsu’

From her two coffins, which are described by Prof. Maspero, we obtain a full list of her offices thus (Wallis Budge, 1912): First head-woman of the secluded women of Amen-Ra, the King of the gods, Chief lady of the Temple of Khensu-em-Uast, Nefer-hetep, Priestess of Amen-Ra, Lord of Aarut, Priestess of Nekhebet the White, of Nekhen, Priestess of Osiris, Horus, and Isis in Abydos, Priestess of Hathor, Lady of Cusae, Divine Mother of Khensu-pa-khart, Chief woman of Amen-Ra, the King of the gods, President (Chief) of the noble women

Niece and second wife of Pinedjem II, mother of Nestanebetisheru. She was the daughter of the lady Takhentdjehuti and of Nesbanebdjed II (Smendes II) the son of the priest-king Menkheperre. Her coffins, most likely originally made for Isetemkheb D, were already stripped of their gold coverings in ancient times, and her heart scarab was stolen by the Abd-el-Rassul family, but it was recovered and taken to the British Museum.

In the Cairo Museum I have counted 30 workers and 11 overseers.

Two shabti boxes (attributed), no photos

Coffins JE 26199 / CG 61030 / SR 10325 in Cairo, see Niwinski 1988, pg. 115

The burial can be dated to c. 981 B.C., Aston pg. 229

Aston mentions three wooden tablets BM 16672 (should be in London, but I can’t find it), Paris E.6858 and Cairo JE 46891 (published in The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 1955 / 12 Vol. 41, The Decree of Amonrasonthēr for Neskhons). There are two other tablets at the bottom of this review of Nesykhonsu

Funerary papyri

BD S.R.VII.11573 – S.R.VII.11485 – JE 26230, Cairo 109

S.R.IV.991 – JE 26228 – CG 58032, see here the Amun decree, Cairo A

The mummy of Nesykhonsu was partly unwrapped by Gaston Maspero on June 27’th, 1886. G. E. Smith completed the unwrapping in 1906. Although Smith could not determine her age at death, he notes that Nesykhonsu had no gray hairs and must have been relatively young when she died. Smith described the face of Nesykhonsu as being narrow, elliptically shaped, and graceful. Both ears had been pierced and Smith observed that the earlobes had been noticeably stretched and lengthened, indicating that Nesykhonsu had frequently worn very heavy earrings. Source The Theban Royal Mummy Project

Wallis Budge writes “It is not quite clear why Nesi-Khensu was such an important personage at Thebes, but there is no doubt that she enjoyed an ecclesiastical authority and wielded a power in that city which was little less than that possessed by the “Morning Star Priestess” i.e., the high priestess of Amen-Ra. She is never called “royal wife,” or ” queen,” and her name is never written in a cartouche. Her position in the palace is indicated by the title “chief of the noble women” which, according to Prof. Naville, means the chief of the women of inferior rank who lived in the royal harem. Among the other titles of Nesi-Khensu is one of considerable interest, namely, Royal Son of Kesh, governor of the Lands of the South

Now, Royal Son of Kesh (Kush) was the title of the Viceroy of Nubia, i.e., of the Egyptian Sudan, and it is nowhere else applied to a woman. Nesi-Khensu was, it is true, a priestess of Khnemu, the Lord of the Cataract Region, but however great her authority may have been at Elephantine and Philae, it cannot have been great enough to justify her calling herself Royal Son of Kesh. None of the priest-kings can ever have exercised effective rule in the Sudan, still less a priestess in the position of Nesi-Khensu. As priestess her chief duties were in connection with the oversight of the secluded women of Amen, who formed a kind of college, and who helped in performing the services in the temple of Amen-Ra.”

Nesykhonsu A

Worker 1, slim specimen

Faience, ca. 17 cm

21st Dynasty, 975 BC

Cairo Museum

Photo: Edward Loring

All around movie of another worker and a rare second one with ear decorations as on her coffin, noticed by a German shabti friend.

Glenn Janes had also brought to my attention that it sometimes appears that some worker shabtis from Nesykhonsu have the earlobe stretched out and that they may also be shown pierced. This rare version does indeed seem to have the same decoration as on her coffin

German private collection

Observation and movies by AB

Courtesy AB 2022

Nesykhonsu A

Worker 3, smaller broad specimen with necklace and bracelet

Faience, ca. 16 cm

21st Dynasty, 975 BC

Cairo Museum

Photo: GJ

Nesykhonsu A

Overseer 1

Faience, ca. 17 cm

21st Dynasty, 975 BC

Brooklyn Museum,

New York

Photo: VB

Research

All around movie of another overseer

German private collection

Courtesy AB 2022

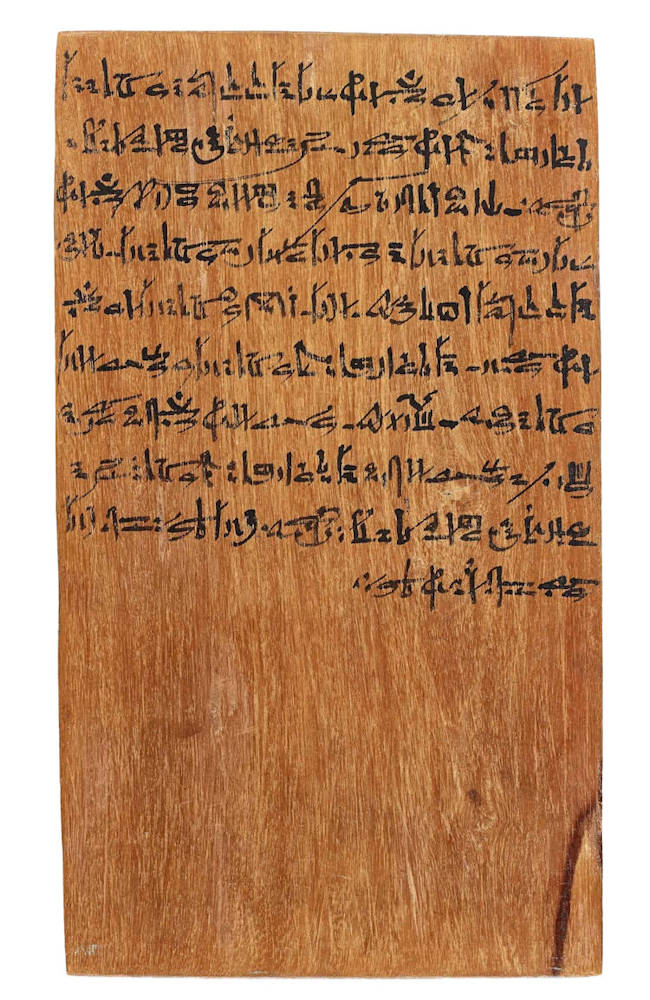

Nesykhonsu (shabti-decree front)

Wood, 28.9 by 16.5 cm

21st Dynasty, 975 BC

‘Two almost identical wooden tablets were found in the Royal Cache DB 320 and are now in the British Museum and the Louvre. They record an oracular pronouncement of Amun that a set of shabtis (servant figures) should work only for their owner, who is consequently exempt from other tasks, and that the ownership of the shabtis is indeed vested in the woman who bought them.’ Source

British Museum, London EA 16672

Photo: VB 2023

Nesykhonsu (shabti-decree back)

Wood, 28.9 by 16.5 cm

21st Dynasty, 975 BC

British Museum, London EA 16672

Photo: British Museum

Nesykhonsu (shabti-decree front)

Wood, 27.9 by 16.5 cm by 1,4 cm

21st Dynasty, 975 BC

Louvre, Paris E6858

Photo: VB

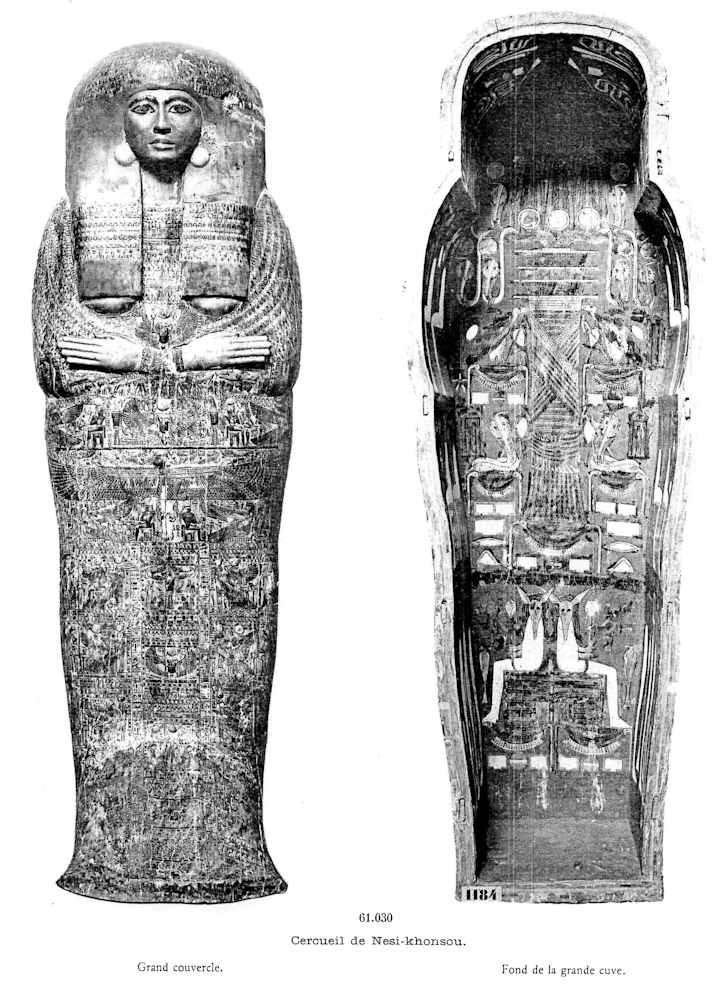

Exterior and interior coffin NesyKhonsu ursurped from Isetemkheb D. Cairo Museum JE 26199 / CG 61030 / SR 10325, numbers on old labels 1184 – 61095 – Sp 10325.

Photo: VB 2015

Georges Daressy’s Cercueils des cachettes royales, 1909. Research

Nestanebetisheru – ns-tA-nbt-iSrw

Also known as Nesitanebashru, Nestanebtashru, Estanebasher

Ranke I, pg. 179, 15

The name means ‘She who belongs to the Lady of Isheru’

According to Wallis Budge, the princess had the following titles: Great lady-in-chief of the secluded women (harem) of Amen-Ra, the king of the gods, Priestess of Amen-Ra, lord of Aaru, Priestess of Nekhebet, the goddess of Nekhen the White (Nekhen was called Eileithyiaspolis by the Greeks, and it was the capital of the Third Nome of Upper Egypt), Priestess of Anher-Shu, son of Ra, Priestess of Pekhthut, the great goddess, lady of Set (a district near Beni Hasan), Priestess of Osiris, lord of Abydos, Priestess of Menu, Horus, and Isis, Priestess of Tcheba (?), the lord of the Nome Antaeopolites, Servant of the books of Amen-Ra, the king of the gods, Singer, of the district of Mut, the great goddess, the lady of Asher (a quarter of Thebes which contained the temple of Mut), President (Chief) of the noble ladies

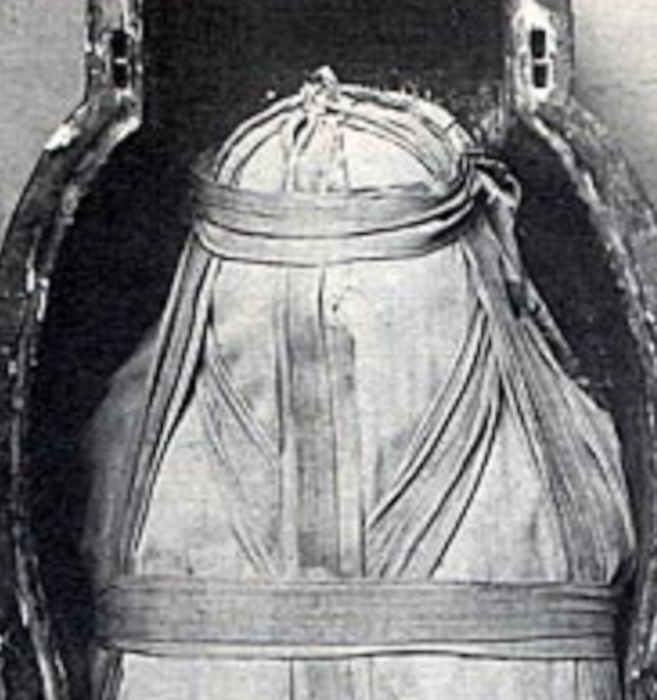

The mummy of Nesitanebtashru was 1 metre 75 centimetres in length, and it was opened on June 30th, 1886. In the swathing’s were found two straps, which were crossed over the breast, and on each of the four leather ends was stamped the following inscription : “Mut, the great lady, the lady of Ashru, the Queen of all the gods”. Under these, folded in four, was a piece of stuff, which seems to have been part of the funerary swathing’s that were made for Queen Ast-em-khebit in the thirteenth year of a king whose name is not given. Dr. Fouquet suggested that Nesitanebtashru was thirty-five or forty years of age when she died

Source of the data above: The Greenfield Papyrus, E.A. Wallis Budge, 1912

Daughter of Pinedjem II and Nesykhonsu. She probably married Djedptahiufankh

In the Cairo Museum I have counted 34 workers and 10 overseers

Coffins JE 26202/ CG 61033 in Cairo, see Niwinski 1988, pg. 115

Two shabti boxes, Cairo Museum JE 46887, JE 46892, no photos

The burial can be dated to c. 954 B.C., see Aston pg. 230

Funerary papyrus

BM 10554, London 61 (Niwinski)

See British Museum, ‘Related objects’ for the frames of the 37 metres long papyrus

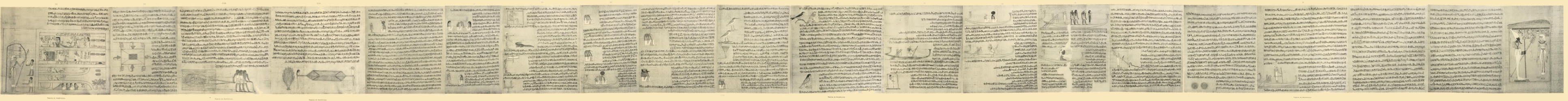

Unrolled Book of the Dead of Nestanebetisheru

The Greenfield Papyrus

Production date circa 950 BC – 930 BC

Panorama view, VB 2021

Nestanebetisheru

Mummy Cairo CG 61096

Smith’s, The Royal Mummies, Cairo 1912, pl. LXXXVIII

See also Les momies royales de Deir El-Bahari, 1889

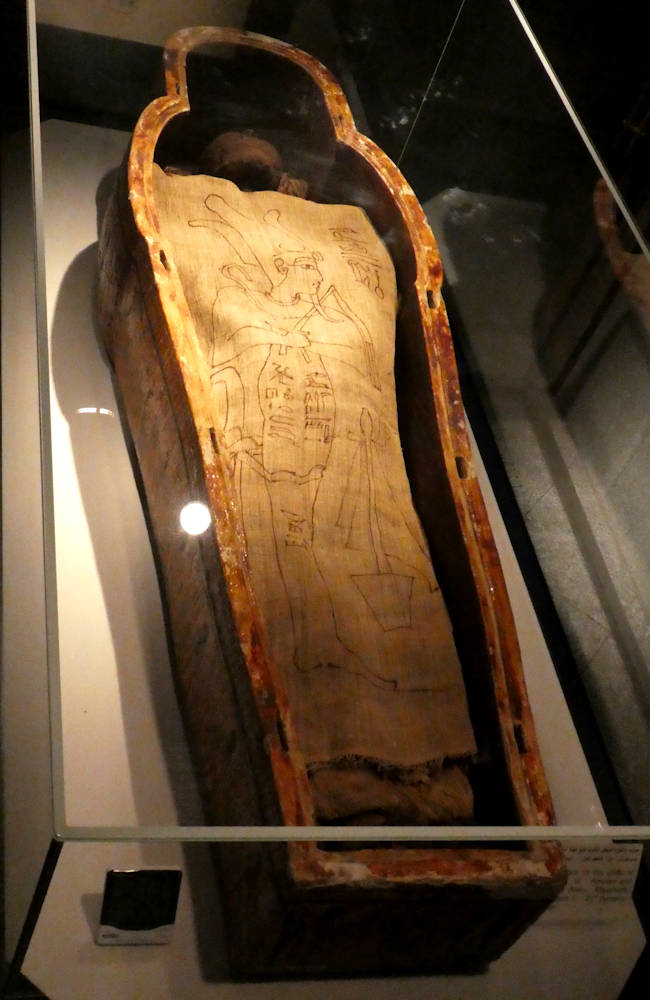

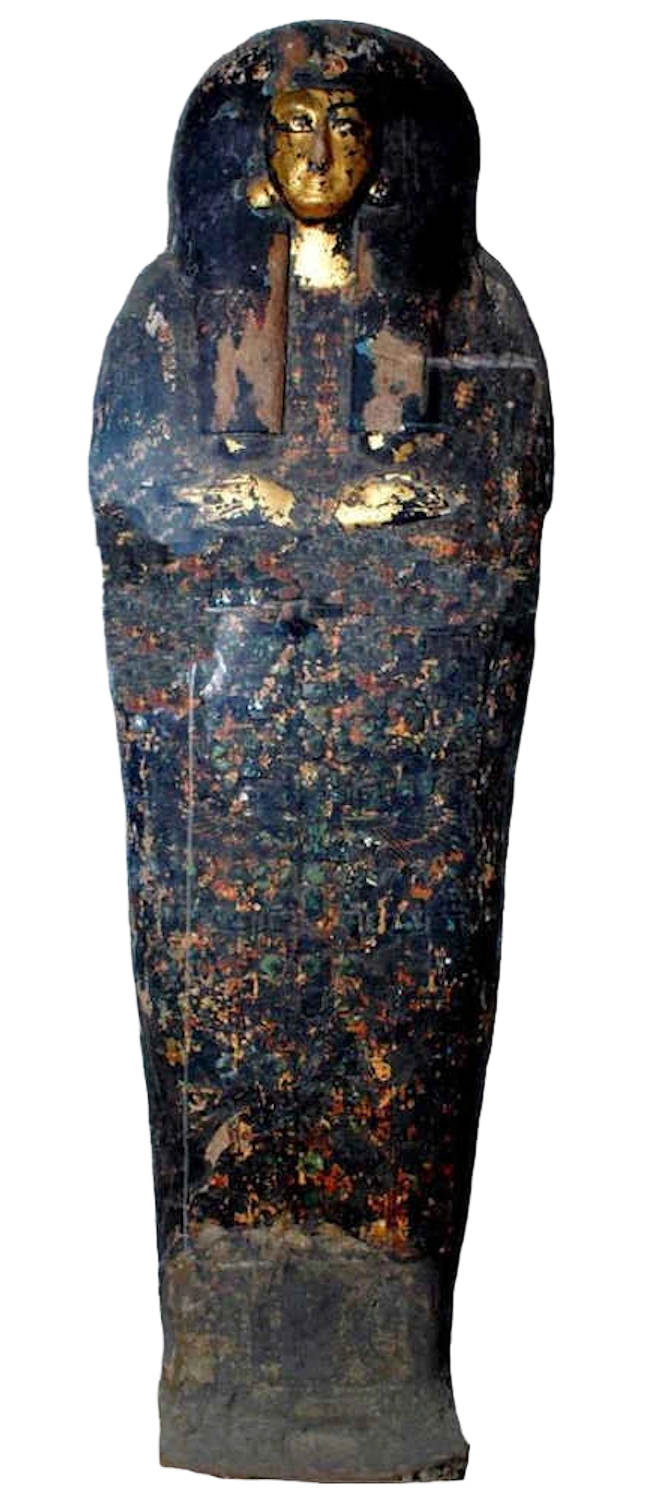

Nestanebetisheru

Exterior coffin Cairo JE 26202 / CG 61033. The decoration of the outer coffin was/is covered with black bitumen. Photo: Cesras.

Nestanebetisheru

Worker 1, dark blue

Faience, ca. 14.5 cm

21st Dynasty, 970 BC

Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden

Photo: VB

All around movie of another worker

German private collection

Courtesy AB 2024

Nestanebetisheru

Worker 2, light blue

Faience, ca. 14.5 cm

7 registers

21st Dynasty, 970 BC

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 1884.50

Photo: VB

All around movie of another well preserved worker

German private collection

Courtesy AB 2022

Nestanebetisheru

Faience, 14.6 cm

21st Dynasty, 970 BC

Private collection UK. Ex Henri Hoffmann Collection, reference: G. Legrain, Collection H. Hoffmann (Paris, 1894) pp. 70-71 [no. 236]

Photo: GJ

The titles on the rare example of the Hoffmann Collection are The Supreme Chief of the Harem of Amen, Priestess of Min [i.e. Akhmim] – Lord of Ipw, Priestess of Osiris – Lord of Abydos, Superior of the Noble Ladies

The hieroglyph’s above and the translation of the titles courtesy Mr. Glenn Janes

Nestanebetisheru

Overseer 1, single column of inscription

Faience, ca. 14.5 cm

21st Dynasty, 970 BC

Musée du Louvre, Paris

Photo: VB

Nestanebetisheru

Overseer 2, double column of inscription

Faience, ca. 14.5 cm

21st Dynasty, 970 BC

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 1884.51

Photo: VB

Exterior and interior coffin Nestanebetisheru Cairo Museum JE 26202 / CG 61033. The decoration of the outer coffin is covered with black bitumen.

Photo: VB 2015

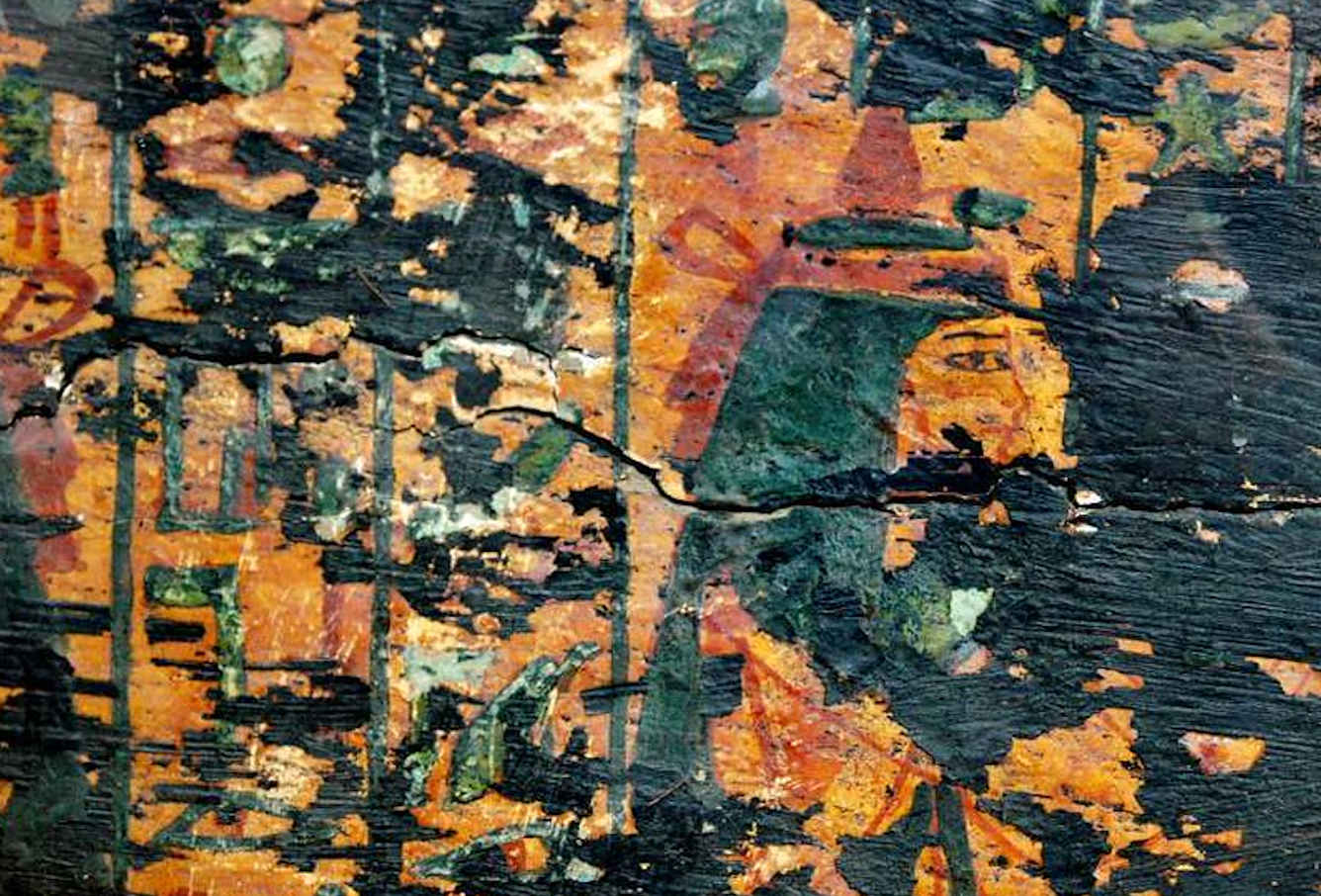

Detail of the outer coffin that is coated with a black substance that obscures most of its inscriptions and decorations

Photo: Edward Loring 2007

Djedptahiufankh – Dd-ptH-iwf-anx

Also known as Djedptahiwfankh, Djedptahioufankh, Zadptahefonkhou

Period c. 969 to 932 BC.

The burial can be dated to c. 932 BC (Aston pg. 231)

Ranke I, pg. 410, 11

The name means ‘Ptah has spoken and he lives’

Djedptahiufankh is only known from his burial and mummy. He held the title of “Second prophet of Amen”, District Governor as well as “King’s Son of Ramesses” and “King’s Son of the Lord of the Two Lands”. The latter may suggest that he was related to the royal family of possibly the 21st Dynasty or 22nd Dynasty

Djedptahiufankh is assumed to be Nestanebetisheru’s husband. This theory is based on the fact that Djedptahiufankh was buried next to Nesitanebetashru in DB320

“The undisturbed condition of his coffins and mummy suggest that he was buried directly in DB320. Thus, he was undoubtedly the last of the Pinudjem-related individuals to be interred there; and it has been suggested that it was probably on the occasion of Djedptahiufankh’s burial that the final reopening of DB320 took place and the deposit of the New Kingdom royal and associated mummies therein was affected.

Gaston Maspero partially unwrapped No. 61097 in 1886, and Elliot Smith completed the job on September 5, 1906, bringing to light a large number of stone amulets and other objects contained within the bandaging. Djedptahiufankh’s fingers and toes also bore several band-like gold rings, which Smith thought had been employed to hold the nails in place during mummification. Maspero had likewise found items of jewellery on the mummy during his partial unwrapping”.

Source: Tombs. Treasures. Mummies. Book Five © Dennis C. Forbes

In the Cairo Museum I have counted 62 workers and 17 overseers. Maspero counted three shabti boxes. Aston writes: “Maspero’s count of the boxes may be wrong; two per burial are the norm, and only one (JE 46886) is recorded in the Journal d’Entrée.” David A. Aston, Burial Assemblages of Dynasty 21-25. No photos.

Funerary papyri

BD location unknown 1

Amun decree, location unknown

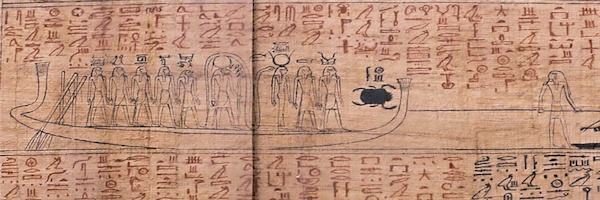

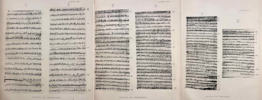

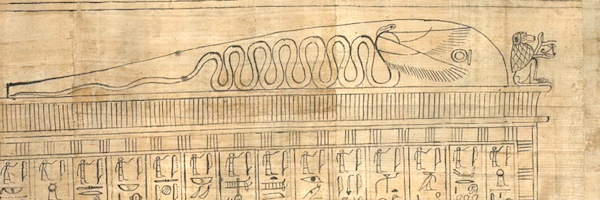

BA S.R.VII.10246, Cairo 83

Amduat papyrus for Djedptahiufankh, Contribution à l’étude de l’Amdouat

See Sadek 1985, C6 Planche 12-13, for description see page 106-110

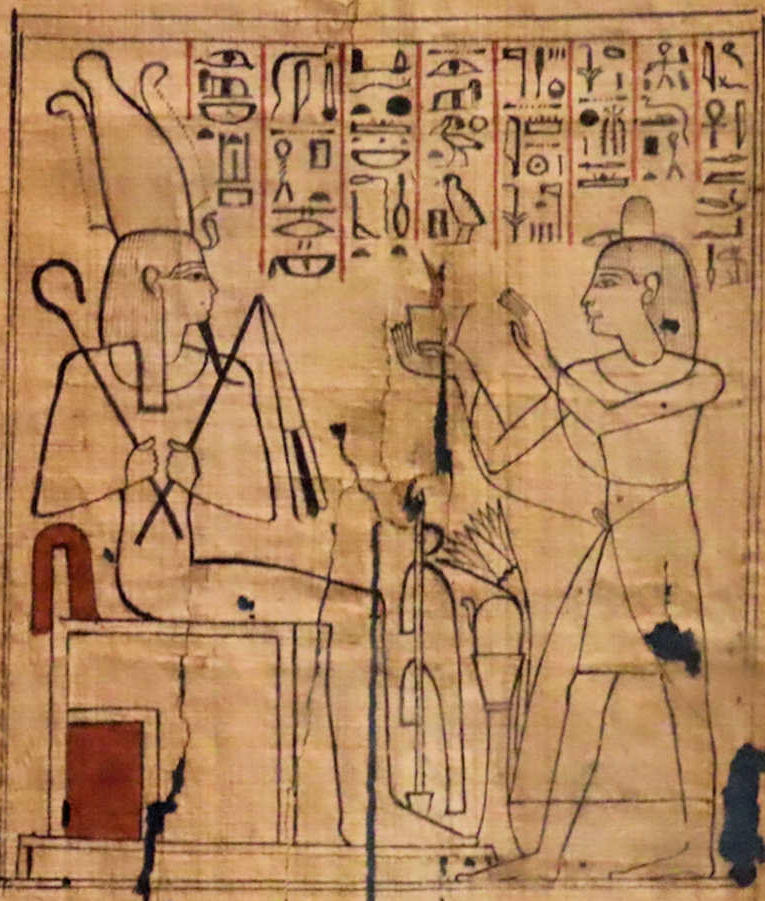

Panorama view, VB 2021

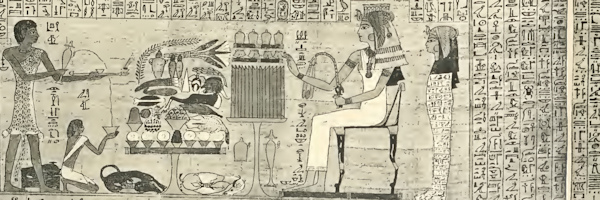

The Etiquette

The label is drawn in black and red, to the right of the composition of the Great Amdouat, which indicates that the papyrus has been rolled up from left to right. The label shows the deceased burning incense before Ptah-Sokar-Osiris. The god, on the left, is seated, in profile and torso facing, on an archaic throne with a red painted cushion and placed on a pedestal. He is wearing the headdress of a Nemes, the uraeus on the forehead, surmounted by the Atef with two feathers indicated in dots. He wears the beard of the gods, and he is clothed with the sticky garment from which the two hands which hold, in the right hand, the crook and, with his left hand, the flail. In front of the pedestal is the emblem of Anubis

The deceased, on the right, stands with a censer in his right hand; his left hand is raised in a gesture of adoration that accompanies the offering. On his head is the perfume cloth and a lotus bud. He is dressed in a short loincloth tied at the waist and in a transparent shirt, falling to the middle of his legs and with raised sleeves. In front of him, a jar with spout and a lotus flower are placed on a gueridon

Contribution à l’étude de l’Amdouat, © Sadek 1985, C6 see Planche 13c, translated from page 108-109

Djedptahiufankh

Worker 1, like worker 2 with column of inscription and priest title

Faience, ca. 11 cm

22nd Dynasty, 935 BC

Cairo Museum

Photo: Edward Loring

Djedptahiufankh

Overseer 1, like overseer 2 with name

Faience, ca. 11.2 cm

22nd Dynasty, 935 BC

Dutch private collection

Photo: VB

All around movie

Dutch private collection

Courtesy AB 2022

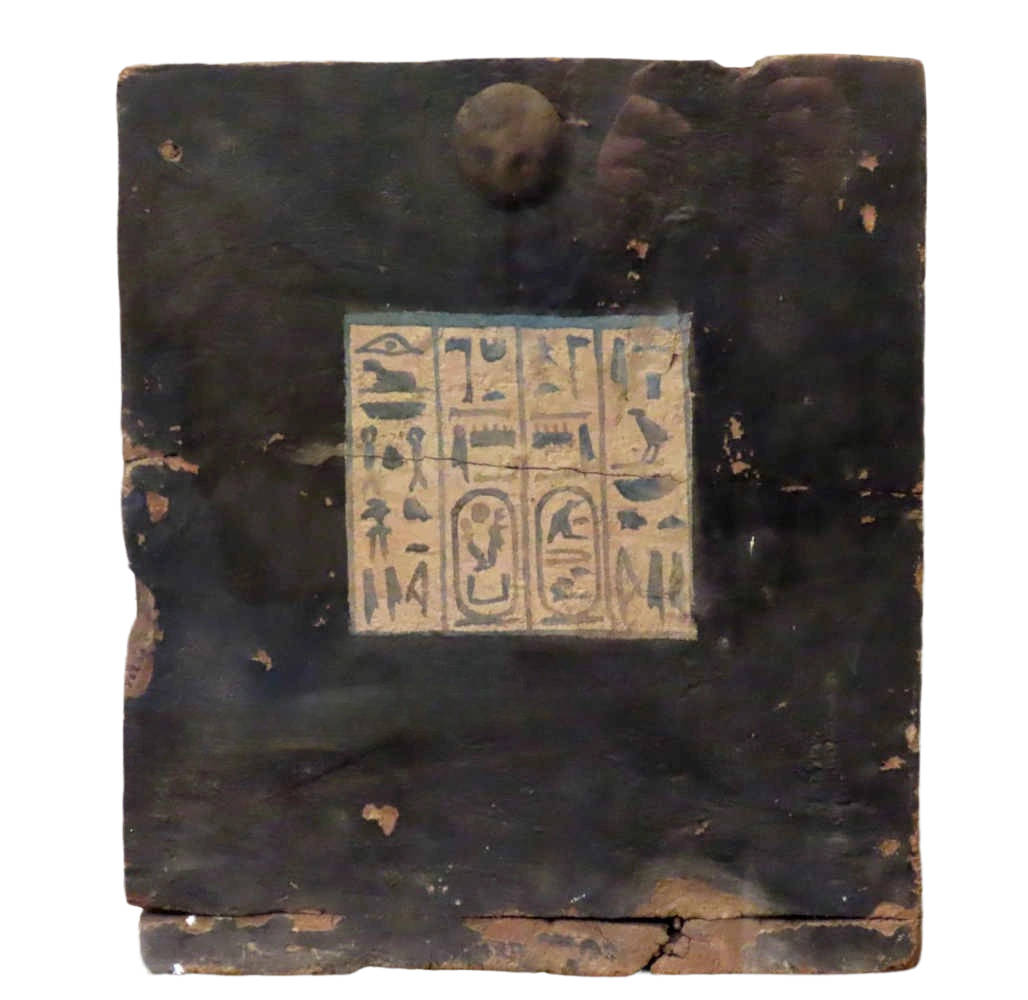

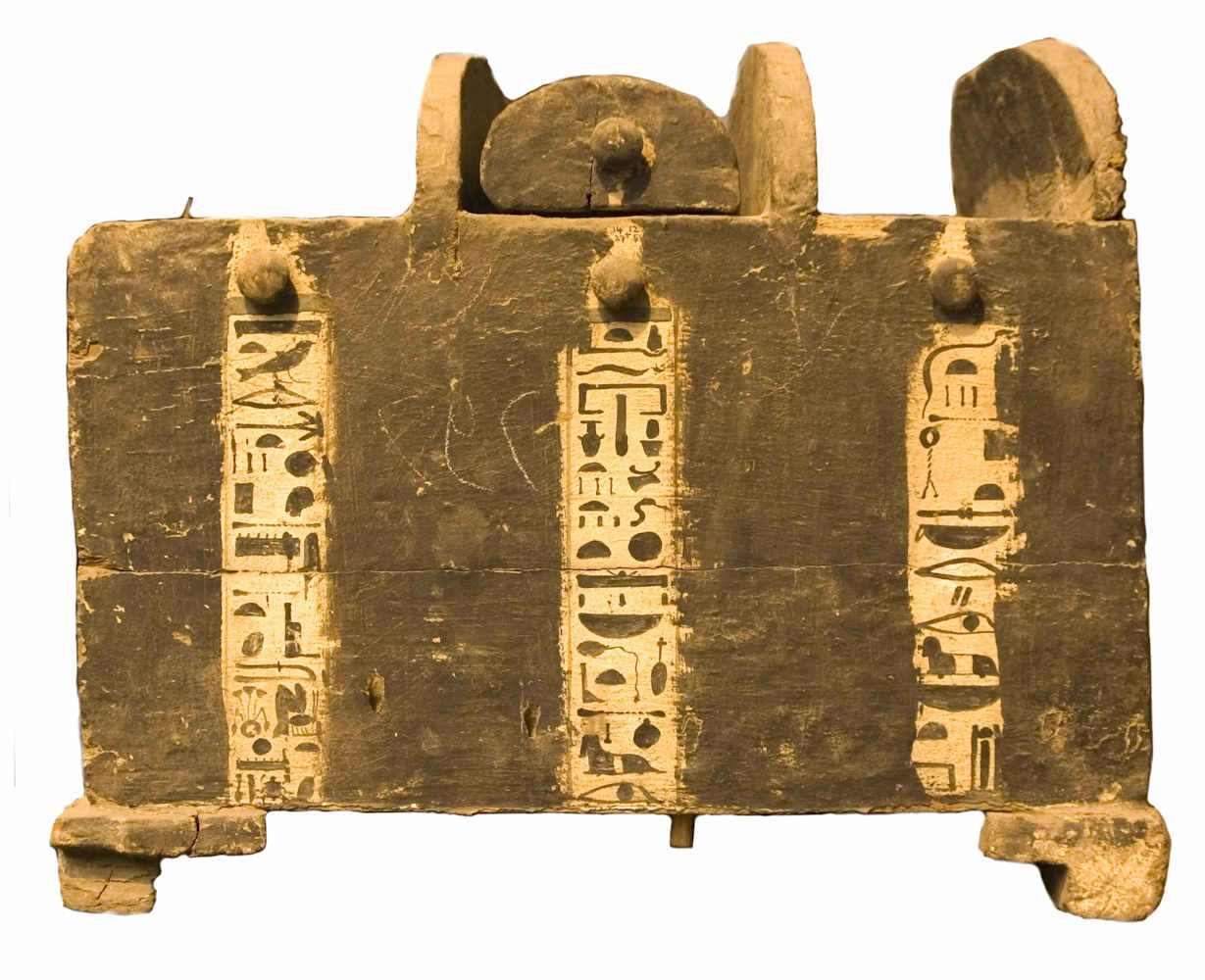

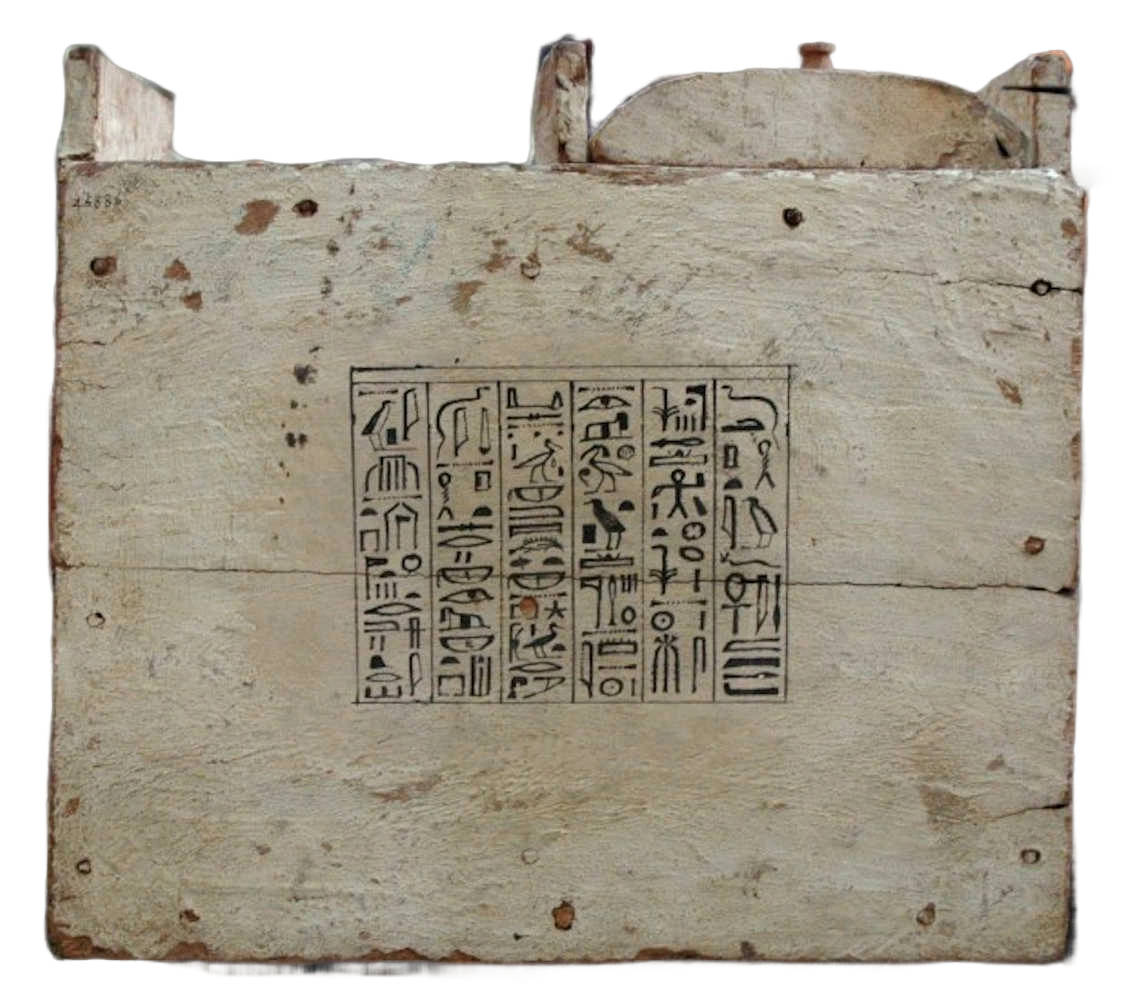

Shabti box Djedptahiufankh (back)

Cairo Museum JE 46886

22nd Dynasty, 935 BC

Cairo Museum

Photo: Edward Loring

Exterior coffin lid Djedptahiufankh ursurped from Nesyshuenopet, Cairo Museum JE 26201 / CG 61034. Photo: Heidi Kontkanen 2016

Georges Daressy’s Cercueils des cachettes royales, 1909. Research

Background info

Gaston Maspero’s notes

The Antiquities Service was founded in Cairo in 1858. From that moment on, it was no longer allowed to dig without a licence or without supervision. In addition, all objects first had to be offered to the new Egyptian Museum. There it was decided which antiquities they would keep, and which objects could go to the finders. The contents of as yet undiscovered graves became the property of the Egyptian government. In reality, however, illegal excavation and trading went on for several decades, and there was nothing the Antiquities Service could do about it.

In 1874 the head of the service, Gaston Maspero, discovered that pieces were appearing on the art market that belonged to owners whose tombs had not yet been found. The cartouches, titles and names pointed to a royal tomb. Maspero knew that the objects had to come from an unlicensed tomb, but he could not find out where it was located. Finally, using an American buyer as a decoy, he traced the objects to the Rassul family from Qurnah. A small village close to the tomb, living on the proceeds of tourism and artefacts sold illegally.

Two brothers, one of whom was Ahmed Abd el-Rassul, the finder of the site, were apprehended and tortured at length. Ahmed would need a cane for the rest of his life. The brothers did not confess and had to remain in custody. On June 25, 1881, the third brother, Mohammed, who had not been arrested, finally decided to disclose the location of the tomb to the authorities on the condition that he would receive a reward.

Since Gaston Maspero, the head of the Antiquities Service, was on holiday in France at that point in time, his assistant, Emile Brugsch, decided to immediately leave the Bulaq museum for Luxor, together with an assistant. Accompanied by the brothers they descended into the shaft of the tomb, where they spent some time revelling at what they had found. The corridors and rooms of the tomb were filled to capacity with boxes, royal mummies and all kinds of funerary items. Straight away, Emile Brugsch decided to empty the tomb as soon as possible in order to protect its contents from further theft. In the end, they managed this in less than 48 hours, with 200 workmen.

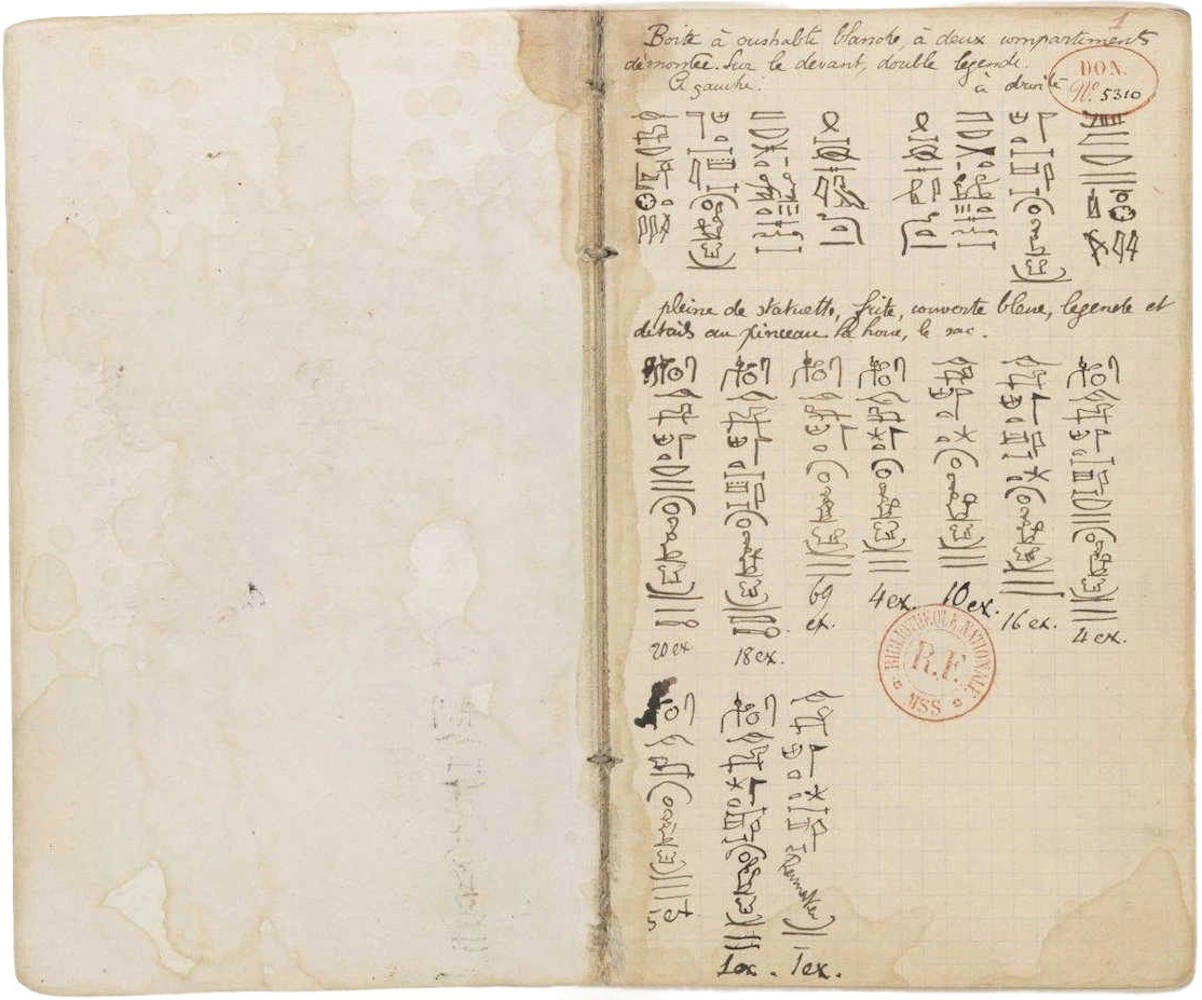

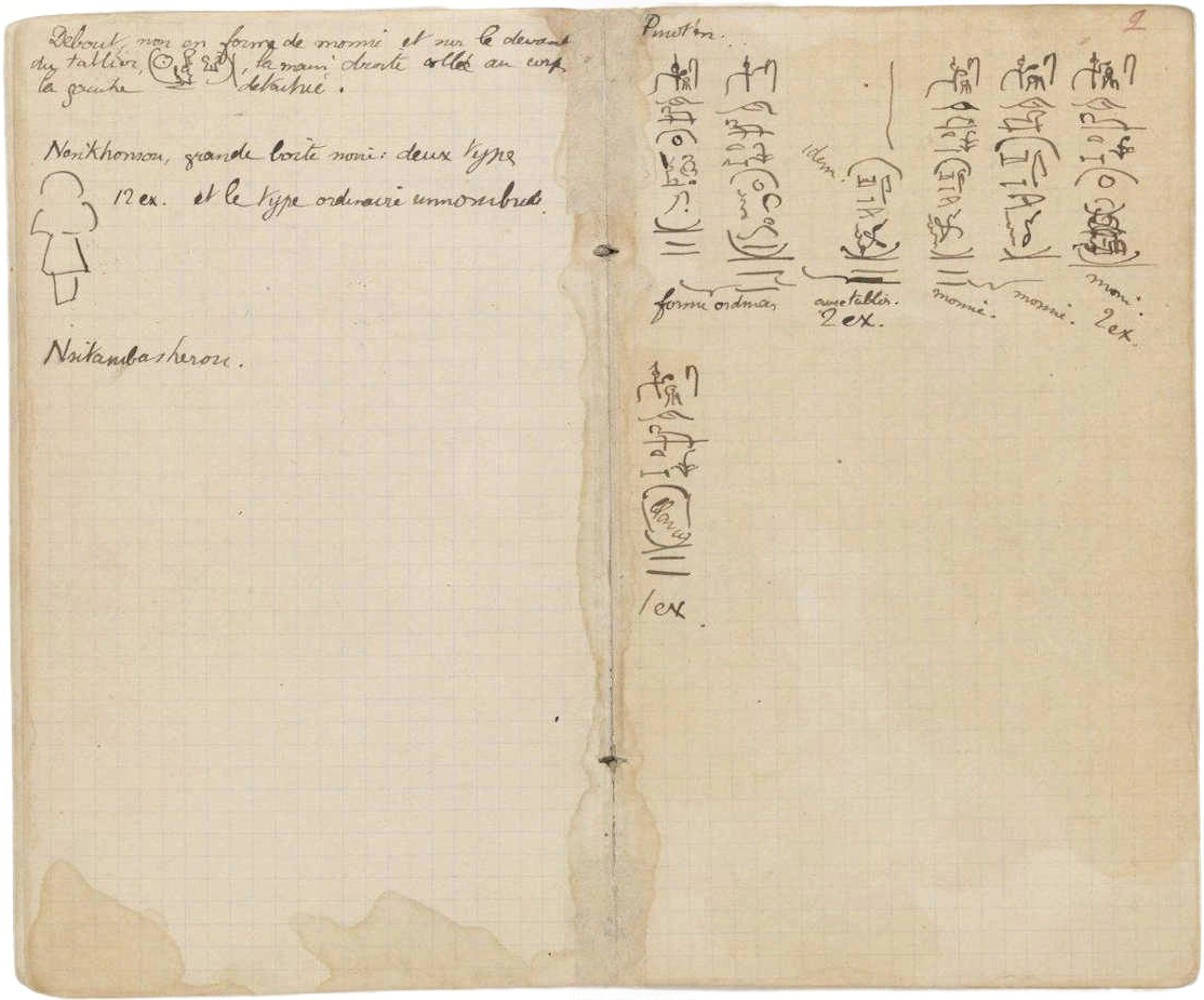

From a scholarly viewpoint this turned out to be a disaster; virtually nothing had been written down, and later on, Maspero had to rely on verbal statements when writing his report. In the Bulaq museum Maspero also researched the shabtis from DB 320, and a number of interesting notes from his research have been preserved. See the accompanying pictures.

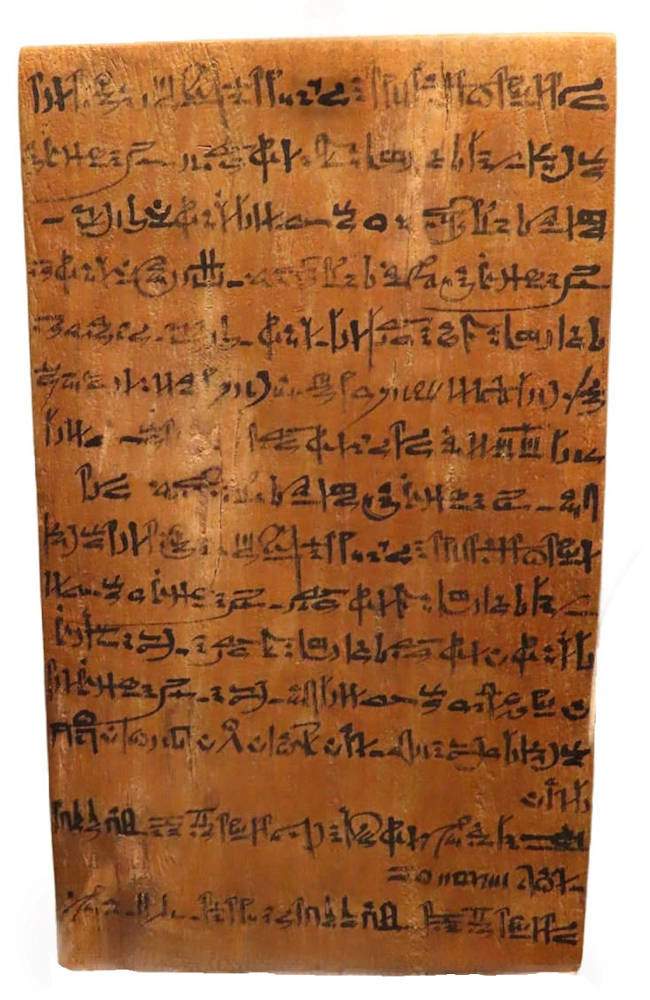

Inventory of a shabti box with inscriptions on top for Maatkara, various inscriptions on the shabtis and a total. Photo: Bibliothèque nationale de France. Cahiers de notes épigraphiques de Gaston Maspero.

The page to the left contains notes about a Maatkara overseer and Nesykhonsu: “Nesikhonsu, large box, two types, 12 ex. (overseers) and full of ordinary type (workers)”. Interesting, because compared with my count one overseer is missing.

Under the drawing we see the name Nestanebisherou. To the right, various inscriptions on the Pinedjem I shabtis, including one with an empty cartouche. This specific shabti is on display in the Cairo museum in front of his shabti box.

Photo: Bibliothèque nationale de France. Cahiers de notes épigraphiques de Gaston Maspero.

Location of DB 320

In 2012 I had the pleasure of visiting the entrance of the tomb, together with the unsurpassed Egyptologist Huub Pragt and the independent shabti researcher Niek de Haan, and I shot a brief holiday video there and included some data and photos from Edward Grafe and George B. Johnson’s article in KMT, volume fifteen, number three, fall of 2004.